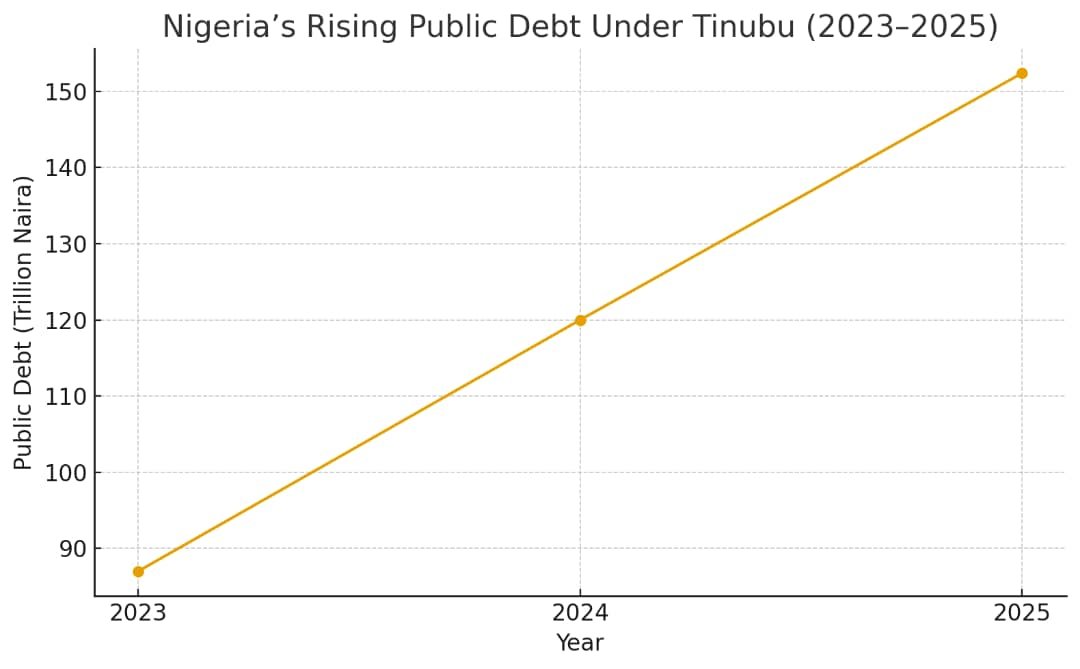

Nigeria’s public debt surged from ₦87 trillion in 2023 to ₦152.4 trillion in 2025, reflecting the fastest accumulation of debt in the country’s history

LAGOS, Nigeria – Despite historic revenue gains from subsidy removal, expanded taxation and FX reforms, Nigeria’s public debt is accelerating at an unprecedented pace under the Tinubu administration. In this report, Korede Abdullah investigates the paradox at the heart of Nigeria’s fiscal strategy, the growing questions over transparency, and the burden citizens now carry for loans they never felt.

A Mountain Higher Than the Climber

Nigeria’s debt has grown so rapidly in the last two years that fiscal watchers now warn the country may be “racing towards a fiscal cliff with its eyes open”.

On 29 May 2023, when President Bola Tinubu assumed office, public debt stood at ₦87 trillion. By June 2025, it had reached ₦152.4 trillion and could cross ₦160 trillion before the end of the year. No administration in Nigeria’s democratic history has accumulated debt at this pace.

Government reforms have indeed boosted revenue, yet borrowing continues to rise—creating a contradiction that has increasingly unsettled economists and citizens alike.

Debt Rising in The Midst of Abundance

Official figures show that domestic debt climbed from ₦54.13 trillion in the second quarter of 2023 to ₦80.55 trillion by mid-2025. External debt rose from $43.16 billion to $46.98 billion in the same period.

The Debt Management Office (DMO) attributes this growth to high domestic interest rates, persistent deficit financing and the naira’s steep depreciation.

But critics argue that these explanations mask deeper structural problems.

A budget analyst with BudgIT, Mr. Gbenga Lawal, put it plainly: “Citizens cannot verify what most of these borrowings are funding, yet they are the ones paying for them through heavy taxation and inflation.”

Transparency Questions Over How Borrowed Funds Are Used

Civil society organisations, including SERAP and the Centre for Democracy and Development, continue to question the opacity surrounding new loans. The government insists borrowings are tied to infrastructure and economic renewal. But many capital projects remain undocumented, uncompleted or inconsistently reported.

Analysts argue that transparency has not improved despite reforms. Instead, they say the public is left with incomplete information about what the fast-rising debt is being used for, and why Nigeria keeps borrowing even as revenue surges.

The Fiscal Paradox: More Money, More Debt

Economic observers remain troubled by the strange alignment of rising revenue and rising debt. Ordinarily, stronger earnings reduce dependence on loans. Nigeria is experiencing the opposite.

In the last two years, the country has recorded: Higher customs receipts, expanded tax nets, improved non-oil revenue, trillions saved from subsidy removal, and increased enforcement by the FIRS. Yet deficit budgets persist.

Public affairs analyst Dr. Tosin Adebayo warns that the country is normalising a worrying trend.

“Nigeria’s problem has never been revenue but disciplined financial management. We are witnessing revenue growth and debt growth rising simultaneously, which is abnormal for a country not facing a recession or natural disaster.”

The Tax Burden: A Citizenry Paying More for A Government Borrowing More

While fiscal indicators show improved earnings, Nigerians say they feel only the pressure of taxation—not its benefits.

The controversial ₦50 stamp duty, new state-level levies, VAT adjustments and attempted cybersecurity charges have hit households and small businesses. Yet public services remain weak, infrastructure gaps persist and inflation continues to erode incomes.

A Lagos businesswoman, Mrs. Sherifat Razaq, spoke to a common frustration: “If all these taxes are being collected, why do we still borrow like a country with no revenue?”

Debt Servicing: Paying For Money Never Seen

Perhaps the most alarming development is how much Nigeria now spends on servicing debt.

By 2024, the debt-service-to-revenue ratio reached 162%, meaning the government spent far more paying creditors than it earned.

Domestic debt servicing jumped from ₦874 billion in the first quarter of 2023 to ₦2.37 trillion by early 2025. External servicing hit $1.39 billion in the same period, largely due to Eurobond coupons and multilateral commitments.

Experts warn that this trend leaves less room for essential services such as health, education and security—effectively punishing citizens for loans they never directly benefited from.

Fx Reforms and The Naira Shock

Tinubu’s move to unify exchange rates was intended to stabilise the foreign exchange market. Instead, the naira’s fall—from around ₦460/$ to beyond ₦1500/$—magnified Nigeria’s external debt overnight.

A financial analyst described the situation succinctly: “The FX reforms ballooned Nigeria’s debt profile by trillions without a single new loan being added.”

What Nigeria owed did not change in dollar terms—but its value in naira exploded.

A Complex Web of Creditors

Nigeria’s creditors mix now includes: The World Bank (about $18.2 billion), The African Development Bank, China, Eurobond investors, and Multilateral and bilateral partners.

Between early and late 2025, the government returned to Eurobond markets twice, raising $4.5 billion at commercial rates. Analysts caution that heavy reliance on costly, non-concessional borrowing exposes the country to:

Interest-rate shocks

Refinancing risks

Currency volatility

The risk is that Nigeria may be borrowing itself into vulnerability.

Should Nigeria Borrow This Much? Experts Disagree

Government officials maintain that borrowing is necessary to build infrastructure, stimulate growth and correct decades of underinvestment.

But critics argue that poor implementation, inconsistent project reporting and weak financial discipline make the pace of borrowing unsustainable.

A fiscal specialist summed up the dilemma: “Nigeria borrows like a rich country but manages finances like a poor one. Without structural reforms, we may be stuck in a permanent cycle of loans.

A Nation at a Crossroads

Nigeria now faces a defining question: Can it reform itself out of a crisis, or is it edging closer to one?

With debt projected to surpass ₦160 trillion, debt servicing consuming large parts of revenue, and citizens increasingly burdened by rising taxes and inflation, economists say the country must choose between:

Genuine fiscal restructuring, strict spending discipline, and transparent use of public funds —or a future where debt overwhelms economic progress.

For millions of Nigerians, the fear is simple: the nation is mortgaging tomorrow faster than it can build it.