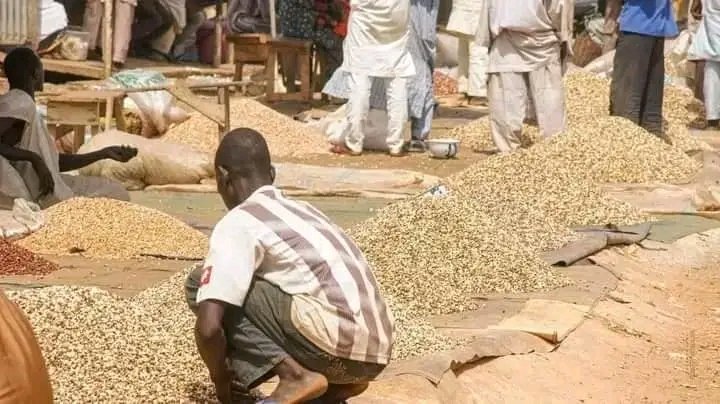

Despite falling grain prices, traders in Kano’s Dawanau Market say buyers have disappeared - a reflection of Nigeria’s deepening income crisis.

KANO, Nigeria – Across the vast markets of northern Nigeria, sacks of maize, rice, and millet now sell for nearly half of what they cost a year ago. But instead of joy, a heavy silence hangs over the stalls. The grains may be cheaper — yet, for millions of families, survival remains as difficult as ever.

In Kano’s sprawling Dawanau International Grains Market — West Africa’s largest food hub — what was once a thundering chorus of traders shouting prices has quieted into anxious whispers. Here, amid towering piles of unsold grain, the paradox of Nigeria’s economy is on full display: falling prices, but empty pockets. Hussaini Ibrahim Kafi, writes.

“Prices Have Dropped, But Buyers Are Not Coming” – Trader

For 42-year-old grain merchant Malam Bashir Abdullahi, the harvest season usually brings brisk business. Not this year.

“Just a year ago, a 100kg bag of maize sold for around ₦60,000,” Abdullahi told Africa Health Report, pointing to stacks of untouched bags behind him. “Today, it’s ₦30,000. A bag of rice that was ₦80,000 now goes for about ₦60,000. Flour and millet have also dropped. But buyers are not coming.”

He sighed, watching an empty truck pull away. “People don’t have money. Even my regular customers who buy for resale say they can’t afford to restock. The problem isn’t supply — it’s purchasing power. When money doesn’t circulate, no matter how cheap things get, nobody benefits.”

“Even ₦5,000 Feels Like ₦500” — Resident

For Hajara Umar, a mother of five living in Bachirawa, the lower prices are meaningless when her husband’s income barely feeds the family.

“Yes, maize flour is cheaper, but we don’t have enough money to buy in bulk,” she explained.

“My husband is a commercial motorcyclist. Sometimes, he comes home with ₦5,000 or less. After buying fuel, how much is left? Even ₦5,000 now feels like ₦500.”

Her words echo a common reality across low-income households in northern Nigeria — where inflation, joblessness, and stagnant wages have stripped families of the ability to afford even basic foods.

“The grains are there,” she said quietly, “but hunger is still in the house.”

Why Lower Prices Don’t Mean Relief

Economists say northern Nigeria’s food crisis is not simply about the price of grains — it’s about a broken system that keeps producers and consumers trapped in poverty.

Dr Abdulnaseer Turawa Yola, an economist at Federal University Dutse, described it as a “production–distribution gap.”

“Farmers are producing, but the benefits are not reaching consumers,” he explained. “Bad roads, high transport costs, and exploitative middlemen mean food prices stay high in urban areas. The same farmers sell cheaply in rural markets but buy other essentials — like oil, soap, and protein — at high prices.”

Yola added that the expected relief from harvests has been blunted by collapsing household incomes. “What we are seeing is a stagnation of purchasing power,” he said. “The rural population produces but earns too little. The urban population depends on them but can’t buy enough. It’s a cycle of poverty feeding itself.”

Quiet Markets, Weak Demand

At Yankaba Perishable Market in Kano, vegetable trader Sani Ibrahim described a harvest season unlike any other.

“It’s harvest time, so tomatoes, onions, and grains are cheaper,” he said. “But we hardly make sales. Customers now buy in cups instead of baskets. Before, people could afford a full basket of tomatoes; now, they only buy half.”

He pointed out that while food items have become cheaper, the cost of everything else — transport, rent, school fees, and fuel — has risen sharply.

“When you finish paying bills, what is left for food?” he asked, shaking his head. “People are tired. Some come to the market to price goods just to know what they can’t afford.”

Experts Warn of “Relief Without Recovery”

Dr Yola calls this new reality “relief without recovery.”

“Yes, supply has improved and prices dropped slightly,” he said. “But when people have no money, it doesn’t translate into real relief. Both rural producers and urban consumers are trapped. That is the danger — when both ends of the economy are weak.”

He warned that if the trend continues, next year’s harvest could worsen. “When farmers can’t sell enough this season, they reduce planting next season,” he said. “That’s how food insecurity spreads.”

According to Yola, the only solution is to inject liquidity and strengthen rural economies. “The government and private sector must support households directly — through social protection, rural credit, and small business funding,” he advised. “Without purchasing power, cheap food is meaningless.”

Beyond the Market: The Human Cost

The paradox of cheap food and persistent hunger underscores a deeper crisis of inequality in northern Nigeria. For families like Hajara’s, each day is a battle for survival.

“Sometimes, we have to choose between food and electricity,” she said. “Even when the market is cheaper, we buy less. We survive day by day.”

Traders like Abdullahi share similar frustrations. “If this continues,” he said, “many of us will leave the business. Prices are down, profits are gone, and customers have disappeared. What kind of economy is that?”

The Poverty of Plenty

Economists often describe Nigeria’s northern markets as an example of “the poverty of plenty” — a situation where abundance exists alongside deprivation.

Despite being the nation’s food basket, the North remains one of the poorest regions. The National Bureau of Statistics reports that more than 60% of households in northern states live below the poverty line. Even when harvests are strong, the benefits rarely reach the people.

The reasons are systemic: poor infrastructure, limited access to credit, and an economy heavily dependent on imports. Without government intervention to boost household incomes, the gap between falling prices and real affordability will only widen.

A Silent Economic Emergency

As dusk settles over Kano’s Dawanau Market, traders begin to cover their goods. The smell of dust and grain fills the air. Buyers are few. The silence speaks louder than any statistic.

For many in the North, this is not just a story about market prices — it’s a story about survival, resilience, and the slow erosion of livelihoods in a region that feeds the nation.

As Dr Yola added, “We have cheaper grains but poorer people. Until Nigerians can afford to buy what they produce, there can be no true recovery.”

The falling prices of grains may seem like good news, but for millions across northern Nigeria, the reality tells a harsher story. Empty pockets, weak income, and silent markets reflect a deeper crisis — one that cheap food alone cannot fix.

Unless urgent action is taken to restore purchasing power, strengthen rural livelihoods, and build economic resilience, the region risks sinking further into what experts now call “the poverty of plenty.”

Grains Are Cheaper, But Hunger Persists: Inside Northern Nigeria’s Silent Economic Crisis