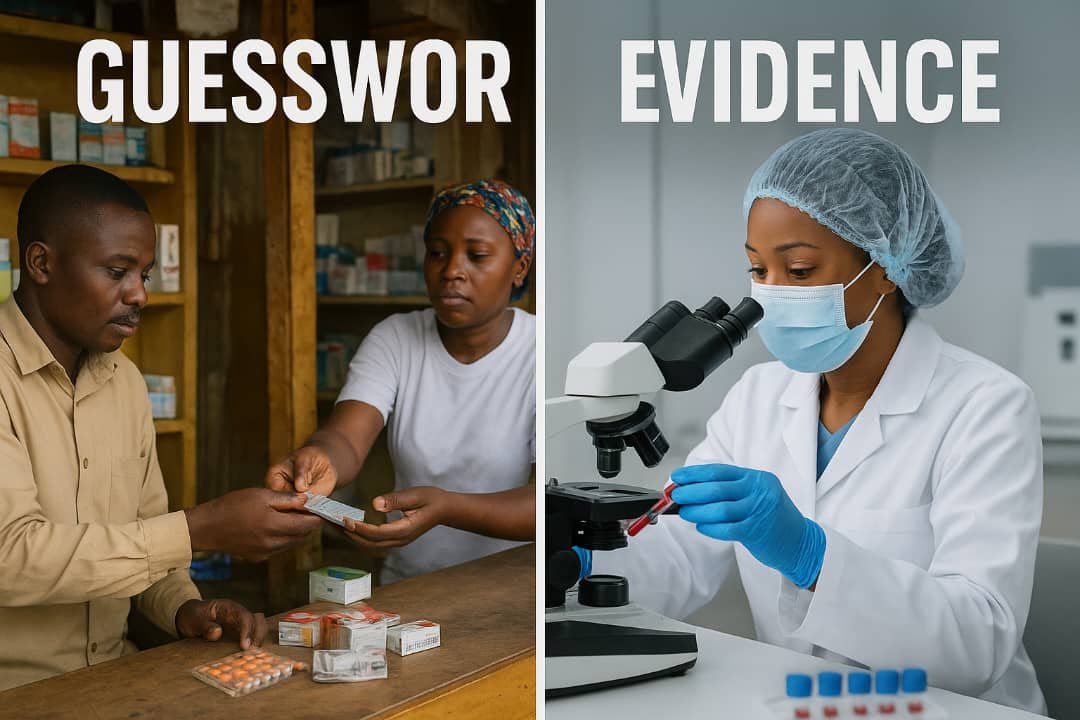

From guesswork to evidence — Nigeria’s health system struggles between symptom-based treatment and laboratory-guided care. Experts say diagnostic testing is the missing link in saving lives and curbing antimicrobial resistance. (Image: AI generated)

ABUJA, Nigeria – As Nigeria faces a rising tide of drug resistance and preventable deaths, a quiet but deadly culture persists in its clinics and chemists — treating before testing. Across cities and rural towns, patients are still prescribed antimalarials and antibiotics based on symptoms alone. Health experts now warn that this “treat-first, test-later” habit is fuelling antimicrobial resistance, wasting billions of naira annually, and silently costing lives.

In this report, Chukwu Obinna explores how a country’s neglect of laboratory diagnostics has become one of the greatest threats to public health — and what must change before it’s too late.

The Cost of Guesswork: Joseph’s Story

For 23-year-old student, Joseph Nnaji, illness was nothing new. Every few months, he would fall sick with fever, weakness, and headaches. Like most Nigerians, he went to a neighbourhood chemist, who handed him malaria and typhoid drugs — no tests, just assumptions.

“I used to get better for two or three weeks, then fall sick again,” Joseph recalled. “I kept treating malaria until one day, I collapsed at work.”

At the hospital, a proper diagnostic test revealed something unexpected — not malaria, but a persistent bacterial infection. After months of mistreatment, his real illness was finally discovered.

Joseph’s story is painfully common. Millions of Nigerians are treated for diseases they do not have, based purely on guesswork. The consequences are severe: prolonged sickness, wasted income, and rising drug resistance that threatens to make treatable diseases deadly again.

A Nation Treating Blind: When Symptoms Deceive

Laboratory diagnostics — the backbone of modern medicine — remain out of reach for most Nigerians. In many hospitals, especially rural clinics, lab facilities are broken, understaffed, or entirely absent.

Simon Uche, a medical laboratory scientist in Lagos, sees the result daily.

“We see patients who have been on three or four drug courses without a single lab test,” he said. “By the time they come to us, their condition has worsened, and we’re dealing with complications that could have been prevented.”

Dr Kizito Daniel, a general practitioner in Ebonyi State, adds that the problem is structural.

“When you’re in a clinic without a lab and a patient is in pain, you do what you can,” he explained. “But symptoms lie. Malaria, typhoid, and viral infections can look identical. Without tests, we’re gambling with people’s lives.”

The Malaria Myth and Misdiagnosis

Nigeria bears roughly 27% of global malaria cases, making it the world’s malaria epicentre. But research increasingly shows that not every fever is malaria.

A 2024 study in Niger State found that only 53% of fever cases tested positive for malaria using rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs). Nearly half of patients treated for malaria had something else entirely.

Uche warns this is a national blind spot.

“We’ve normalised giving antimalarials for every fever. But when we test, we often find it’s typhoid, urinary infections, or viral illnesses,” he said. “The tragedy is double — patients spend money on the wrong drugs while their real illness worsens, and drug resistance grows.”

Antimicrobial Resistance: A Ticking Time Bomb

The World Health Organisation has called antimicrobial resistance (AMR) one of the greatest global health threats. In Africa, Nigeria has one of the highest mortality rates from resistant infections — 27.3 deaths per 100,000 people, according to the Africa CDC.

Dr Daniel warns bluntly: “AMR is a ticking time bomb. We’re already seeing infections that don’t respond to first-line antibiotics. If we don’t test before treating, we’ll soon face diseases we can’t cure.”

Uche’s lab results confirm the fear.

“We see bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics,” he said. “When you trace the history, the patient had been on random antibiotic courses without testing. The bacteria kept evolving.”

Nigeria’s Second National Action Plan on AMR (2024–2028) aims to reverse this trend — but without routine diagnostics, experts say the plan will falter.

The Hidden Economic Cost

Beyond the health damage, the diagnostic deficit carries a heavy financial burden. Families spend thousands on ineffective drugs and repeated treatments, draining savings and productivity.

Dr Daniel explained:

“A ₦5,000 test could save ₦50,000 in wrong treatments and lost income. But most Nigerians pay out of pocket for healthcare. They skip the test because it feels expensive — not realising it’s cheaper than trial-and-error treatment.”

According to the World Bank, more than 70% of Nigeria’s healthcare expenses are paid directly by patients — one of the highest rates globally. The result is a vicious cycle of self-medication, delayed testing, and failed treatment.

Diagnostics Infrastructure: Unequal and Underpowered

Nigeria’s diagnostic landscape improved during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 73 accredited private and corporate testing labs established by 2023. Yet, the gains are uneven.

Dr Daniel, who serves a largely rural population, says the disparity is glaring.

“If I tell a patient to travel 50 kilometres for a test, they simply won’t go,” he said. “They can’t afford transport or lab fees. So we treat based on symptoms and hope for the best.”

Most diagnostic centres remain concentrated in Lagos and Abuja, leaving rural states with broken machines and scarce reagents. Even where equipment exists, frequent blackouts cripple testing.

Uche calls for decentralisation: “Every local government should have a functional lab. Rapid tests for malaria, typhoid, and infections should be standard in all PHCs. Community health workers can be trained to use and interpret them.”

Policy Frameworks Without Power

Nigeria made history in May 2022 by launching Africa’s first National Essential Diagnostics List (NEDL) — a WHO-backed roadmap outlining 145 priority tests, from HIV to tuberculosis.

Dr Daniel praises the initiative but questions its implementation. “It’s a game-changer on paper,” he said. “But most hospitals don’t even have half the listed tests. There’s no sustainable funding or monitoring system to make it real.”

Experts also point to the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) as a potential vehicle for reform. Expanding insurance to cover essential diagnostics could make testing affordable for millions.

Public Awareness: The Missing Link

Health workers agree that technical reforms alone won’t solve the problem — citizen awareness must rise too.

Joseph, now fully recovered, has become an unlikely advocate.

“I tell everyone: test before you treat,” he said with conviction. “A simple test saved my life.”

His message underscores a growing movement among patients and professionals who see diagnostics as the real foundation of Universal Health Coverage.

Test, Not Guess

Nigeria’s health system stands at a defining crossroads. With committed laboratory scientists, new diagnostic policies, and private sector innovation, the tools for change exist. What’s missing is political will and sustained investment.

Dr Daniel delivers a sobering truth: “Politicians love commissioning hospital buildings. But a hospital without a lab is like a car without an engine — it looks fine, but it can’t move.”

Uche adds, “Every day we delay, people die from misdiagnosis. Every day we skip testing; we breed drug resistance. Testing should be as automatic as prescribing.”

The way forward is clear: equip every primary health centre, train more laboratory staff, subsidise essential tests, and launch a national campaign urging Nigerians to demand testing before treatment.

Because, as Uche puts it: “In medicine, assumptions kill — evidence saves. If Nigeria truly wants to save lives, it must learn to test, not guess.”