Pupils at a rural primary school in Kano sit in a classroom with scarce resources, as poor internet connectivity deepens education inequality.

KANO, Nigeria – Nigeria is sprinting toward ambitious broadband goals, yet in farming towns like Durbunde, Takai Local Government Area of Kano State, the race feels like a cruel mirage. While over 107 million Nigerians are online, about 128 million remain excluded, mostly in rural areas.

In this report, Hussaini Ibrahim Kafi journeys into Durbunde to expose the harsh realities of digital exclusion—stories of young people whose dreams are deferred, teachers battling resource gaps, farmers missing economic opportunities, and families left stranded in a world where connection defines survival.

This is not just about internet access. It is about the future of education, commerce, and social mobility in rural Nigeria.

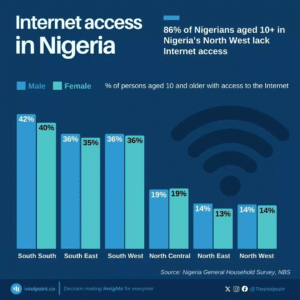

The Digital Divide: Numbers that Tell a Story

At the start of 2025, Nigeria’s internet penetration stood at 107 million users. The other side of that number 128 million offline citizens—reveals the hidden crisis of digital exclusion.

Rural areas like Durbunde remain the hardest hit. Despite its reputation as a rice-producing hub with bustling small businesses, this farming community of fewer than 20,000 residents remains digitally stranded just 15 kilometres from Takai town and 100 kilometres from Kano city.

For residents, this proximity to urban centres brings no relief. Connectivity is weak, inconsistent, and often absent, leaving communities disconnected from both government programmes and the modern economy.

Dreams Deferred: Hussaini Aliyu’s Story

For 26-year-old Hussaini Aliyu, connectivity was not just about browsing social media—it was about changing his life.

“I once dreamed of studying political science to become a politician,” he recalled. “But in Durbunde, there were no facilities, no internet, no opportunities.”

Forced to relocate to Kano city, Aliyu juggled school with farming and menial jobs. “Sometimes I worked at building sites just to eat. Life was too hard, and I gave up on education,” he admitted.

Today, he works at a rice processing company in Tokarawa, but he still clings to the hope of returning to school. His story symbolises the quiet tragedy of digital exclusion: ambition crushed not by lack of talent, but by lack of opportunity.

Teachers Speak: Education in the Dark

At Durbunde Primary School, Headteacher Adamu Muazu faces a daily struggle. With no reliable connectivity, both teachers and pupils are trapped in a vicious cycle of disadvantage.

“Because of poor connectivity, we lose access to many federal government programmes and essential services,” Muazu explained. “Sometimes we travel 15 kilometres just to connect or wait until midnight when the weak signal improves.”

Pupils are the worst hit. With limited textbooks and no access to online materials, rural children fall further behind their urban peers. Complaints have been written “at least a hundred times,” Muazu said, “but nothing has been done.”

Children Left Behind: Aisha’s Silent Struggle

For 14-year-old Aisha Ibrahim, the digital gap is not an abstract policy issue. It shapes her daily life.

“I sometimes miss submitting assignments because I can’t access materials on time,” she said softly. “It makes me feel like I’m not as smart as the other students in town.”

Her words capture the silent despair of thousands of rural schoolchildren across Nigeria who are punished not for laziness, but for being born in the wrong postcode.

A Governor’s Visit, A Community’s Plea

On 7 August 2025, when the Kano State Governor visited Takai General Hospital for a nutrition programme, residents of Durbunde seized the moment.

“We told him how our children cannot learn, and our businesses cannot grow without connectivity,” said Mallam Sani Ibrahim, a farmer.

Weeks later, with no feedback or intervention, hope is fading. “It makes us feel forgotten,” Ibrahim added.

Farmers Shut Out of Digital Markets

For rice farmer Malik Usman, digital exclusion has direct economic costs.

“We can’t reliably check market prices or send photos of produce to buyers. By the time I manage to connect, deals are already gone,” he lamented.

In a world where agriculture increasingly depends on digital tools for pricing, logistics, and supply chain management, Durbunde’s farmers remain stuck in an outdated system—despite feeding thousands.

Policy Promises, Broken Delivery

Nigeria’s National Broadband Plan (2020–2025) promised 70 per cent broadband penetration by December 2025. Alongside it, the Universal Communication Access Project aimed to connect 21 million people in 4,834 unserved communities.

But in places like Durbunde, these targets feel like distant slogans. At the Digital Industrial Park in Kano, officials acknowledge structural failures.

“We have the plans and policy support,” said Director Muhammad Imran, “but execution suffers when operators see no incentives to extend coverage to rural areas. Unless rural access becomes a deliberate priority, many communities will stay excluded.”

Beyond Coverage: The Usage Gap

Experts stress that digital exclusion is not just about coverage—it is also about affordability and usage. Even in areas with network presence, millions cannot afford smartphones or data.

This “usage gap” is particularly wide in northern Nigeria. In Kano State, home to over 16 million people, thousands of rural communities remain cut off. The result is entrenched inequality—between rich and poor, urban and rural, connected and excluded.

The Stark Irony: Food Producers Without Digital Access

The irony is undeniable: communities like Durbunde feed the nation yet cannot feed into the digital economy. Their rice sustains markets across Nigeria, but their children cannot Google their homework.

Unless interventions move from paper to practice, millions risk permanent exclusion. Experts call for last-mile infrastructure, rural data subsidies, and community internet hubs powered by renewable energy.

A Future at Risk

The digital divide in rural Kano is not just about dropped calls or slow browsing. It is about stolen futures. It is about children like Aisha left behind young men like Hussaini forced to abandon education, and farmers like Malik locked out of modern markets.

As Nigeria races toward broadband expansion, communities like Durbunde remind us that connectivity is not a luxury—it is a lifeline.

Unless deliberate action is taken, the dreams of millions will remain deferred, and the nation’s ambition for inclusive digital growth will collapse under the weight of its own neglect.