ABUJA, Nigeria – Cervical cancer should no longer exist as a death sentence. The science to prevent it is proven, the tools are available, and the roadmap is clear. Yet across much of the developing world, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, the disease continues to claim lives quietly, disproportionately and needlessly. Each year, hundreds of thousands of women die from a cancer that is almost entirely preventable. Their deaths are not the result of medical impossibility but of systemic failure — gaps in access, awareness, funding and political will.

As Cervical Cancer Awareness Month renews global attention on this crisis, in this report, Gladness Otamere, examines why cervical cancer persists, where progress is being made, and what must change to eliminate one of the world’s most preventable killers. Central to this report is an exclusive interview with a Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH), Dr. Maradona Isikhuemen. A leading authority on women’s health in Nigeria, Dr. Isikhuemen offers insight into science, the failures and the possibilities.

“Cervical cancer doesn’t happen overnight; it has a very clear pre-malignant phase which we could identify and treat to prevent it,” he explains.

His words frame a story that is as much about hope as it is about urgency.

The Global Burden: Inequality Written in Statistics

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide, yet its impact is far from evenly distributed. In 2022, an estimated 662,301 women were diagnosed, and around 350,000 died. Alarmingly, 94 per cent of these deaths occurred in low- and middle-income countries.

Sub-Saharan Africa carries the heaviest burden, with incidence rates reaching 40 cases per 100,000 women in parts of Eastern Africa. The disease thrives where healthcare systems are weakest and where women are least likely to be screened or vaccinated.

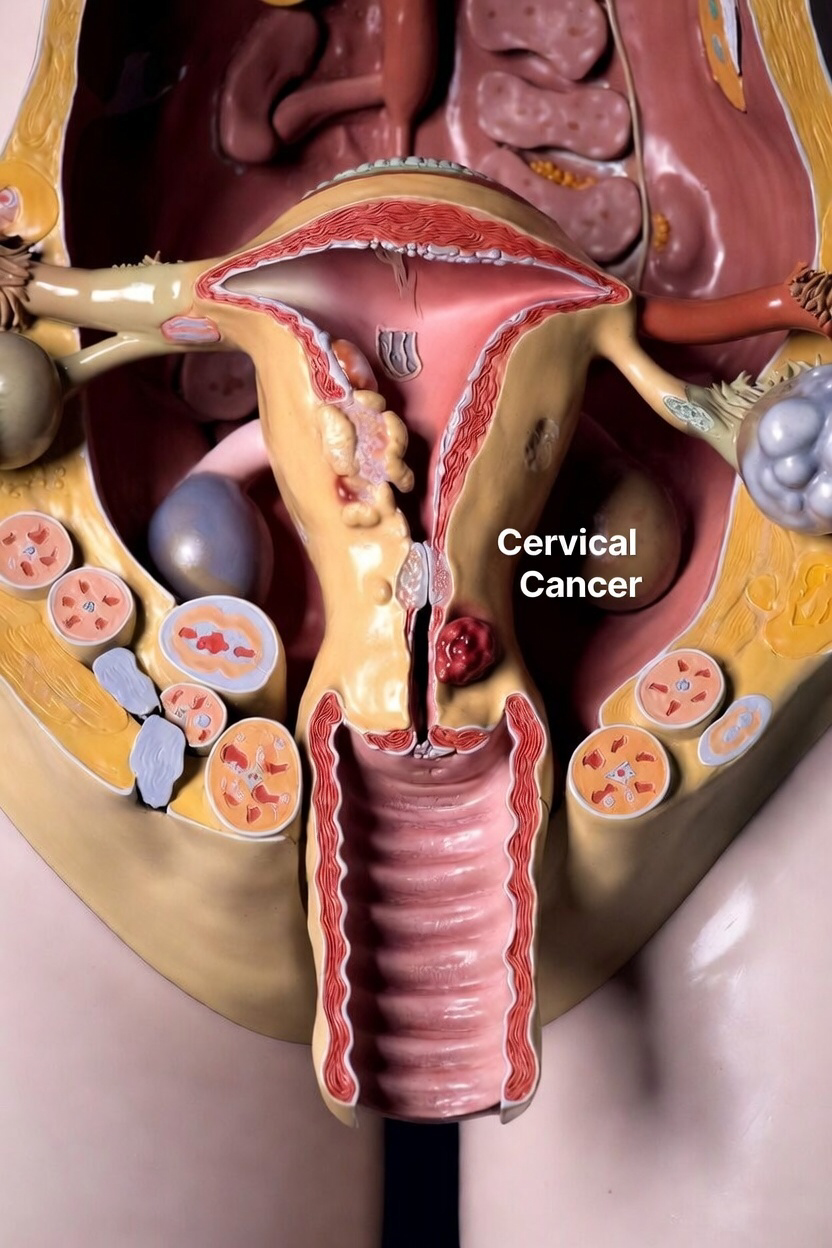

At the root of nearly all cases is the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common sexually transmitted infection.

“The primary cause of cervical cancer is HPV, a sexually transmitted virus which is now involved in the majority of cervical cancer cases,” Dr. Isikhuemen explains.

“I must state that HPV is ubiquitous, everywhere, but most times the body clears it off… Very few will have persistent infection, and few with persistent infection will have cervical cancer.”

This biological reality makes cervical cancer uniquely preventable — if detection and prevention systems function.

WHO’s Elimination Strategy: A Global Blueprint

Recognising this preventability, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched its Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer in 2020. The ambition is historic: reduce incidence to below four cases per 100,000 women worldwide.

The strategy is anchored on the 90-70-90 targets by 2030:

90% of girls fully vaccinated with the HPV vaccine by age 15

70% of women screened with high-performance tests by ages 35 and 45

90% of women with pre-cancer or cancer receiving appropriate treatment

Endorsed by 194 countries, the framework is widely viewed as achievable — but only with sustained investment.

Dr. Isikhuemen stresses the importance of layered prevention.

“For women who are sexually active, it’s important to employ secondary prevention… If detected at the pre-malignant stage, it can be completely cured.”

Progress and Gaps: A World Moving at Uneven Speed

Globally, progress is real but uneven. By 2025, more than 86 million girls had received HPV vaccines through Gavi-supported initiatives. Seventy-five countries have adopted single-dose schedules, reducing cost and logistical barriers.

Yet inequity persists. Only 46 per cent of low-income countries have national HPV vaccination programmes, compared to 98 per cent in high-income countries.

Africa sits at this crossroads of promise and peril.

Nigeria’s Paradox: Momentum Amid Fragility

Nigeria illustrates both the potential and the fragility of elimination efforts.

The country ranks seventh globally in cervical cancer cases. In 2023, there were 13,676 new cases and 7,093 deaths. More recent estimates suggest the toll is even higher — 14,943 cases and 10,403 deaths annually, making cervical cancer the second most common cancer among Nigerian women.

Despite this, Nigeria has launched an ambitious national drive. Since integrating HPV vaccines into routine immunisation in 2023, over 12.26 million girls have been vaccinated, with a target of 16 million by 2025, backed by funding support from the First Lady’s office.

Screening, however, remains critically low — around 5.3 per cent.

“Even when you detect the disease, some centres might not have the facilities to treat the pre-malignant phase,” Dr. Isikhuemen says.

Most screening in Nigeria is opportunistic rather than systematic, meaning women are often diagnosed late — when treatment is more complex and costly.

Risk Factors and Late Presentation

Several socio-economic and behavioural factors drive Nigeria’s burden.

“There are certain behaviours that place women at risk, including multiple sexual partners, immunosuppression like HIV, early sexual intercourse, low socio-economic status, and avoidance of condom use,” Dr. Isikhuemen explains.

Late presentation often rules out surgery, forcing patients into prolonged chemoradiation — financially and emotionally devastating.

“The issue of cervical cancer awareness in Nigeria stems from ignorance, poverty, low socio-economic status, coupled with contributions by the system,” he adds.

“They cannot provide a functioning screening programme for women.”

Prevention Science: Simple Tools, Powerful Impact

The science behind prevention is straightforward.

Primary prevention relies on HPV vaccination, ideally between ages 9 and 14.

“There is an HPV Vaccine which we are clamouring for… Especially at Age 9-14. It can be given later than that but it’s better to give at an earlier age,” Dr. Isikhuemen says.

Secondary prevention focuses on screening — from Pap smears and HPV DNA testing to low-cost methods such as visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA).

“We have cheaper methods for places like Nigeria such as Visual inspection with Acetic acid,” he notes.

Treatment of pre-cancerous lesions can take minutes, using thermal ablation or cryotherapy — a stark contrast to late-stage care.

Voices from the Street: Awareness Still Alarmingly Low

Interviews in Abuja reveal how far awareness still lags. Several residents admitted they had never heard of cervical cancer. Others knew only that “cancer kills”.

MK, who lost her mother to the disease, represents a different reality.

“I’ve been aware in my early stage because I lost my mom to the disease. I have taken the HPV vaccine, and I also go for screening every six months.”

Online surveys echo this divide: 50 per cent have superficial knowledge, 20 per cent deeper understanding, while another 20 per cent know nothing at all.

Survivors and Signals of Hope

Across Nigeria, survivors are becoming advocates. Sarah Abok, diagnosed in 2021, now champions vaccination in Plateau State. Franca Eze, another survivor, founded a non-profit to protect future generations.

Their stories mirror a growing truth: cervical cancer can be beaten.

The Road Ahead: Turning Strategy into Survival

Experts agree the path forward is clear:

Expand single-dose HPV vaccination

Integrate screening into primary healthcare

Scale self-sampling HPV tests

Invest in sustained, community-led awareness

“A few months ago, the vaccine was not available, but recently… it’s relatively available,” Dr. Isikhuemen says.

The opportunity is here. The cost of delay is measured in lives.

A Test of Global Will

Cervical cancer elimination is no longer a scientific challenge — it is a moral one. The tools exist. The roadmap is drawn. What remains is the will to act.

If governments, health systems and communities move in unison, a generation of women could live free from a disease that should never have claimed so many.