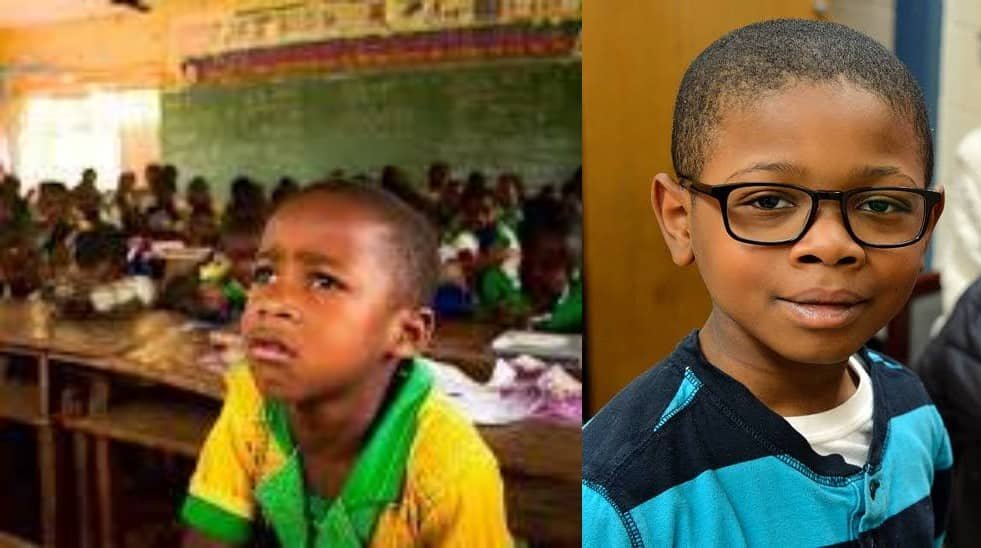

ABUJA, Nigeria – When ten-year-old Chidi squints from the back of his Abuja classroom, the blackboard dissolves into blurred scribbles. He rubs his eyes, fights headaches, and quietly falls behind. For children like him, an untreated eye problem is not just a health challenge, it is a thief of opportunity.

In Nigeria today, thousands of schoolchildren silently endure similar struggles, their education stunted by preventable vision impairments. Experts warn that without urgent, systematic action, the nation risks raising a generation unable to reach its full academic or economic potential.

In this report, Juliet Jacob, explores the neglected crisis of childhood eye health—its roots in poverty and policy failure, it’s devastating impact on learning, and the urgent solutions that could help millions of children see a brighter future.

A Crisis in Plain Sight

Globally, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates 12 million children live with vision impairments correctable with glasses. For Nigeria, the numbers are stark. Studies suggest 15–20% of schoolchildren suffer refractive errors such as myopia or hyperopia, yet only one in ten receives the help they need.

The country has fewer than 7,000 practising optometrists, most clustered in major cities, leaving rural and peri-urban schools almost untouched by screening initiatives. Poverty, weak infrastructure, and poor public awareness worsen the situation.

The implications are enormous. Education, enshrined in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4, cannot thrive if pupils cannot see. Likewise, SDG 3 (Health) is undermined when childhood blindness and visual impairment remain untreated. Unlike wealthier nations, where early checks and affordable spectacles are routine, Nigerian children often struggle unnoticed—until academic failure exposes their hidden disability.

Voices from Families and Classrooms

For parents like Mrs. Ruth in Abuja, her six-year-old’s diagnosis of short-sightedness came as a shock.

“He squinted at the board and rubbed his eyes nonstop. We’ve upgraded lenses twice, but the costs—₦20,000 to ₦50,000 per pair—are a heavy burden.”

In Kubwa, Mrs. Judith recalls dismissing her daughter’s persistent headaches as “stress”. It was only after a teacher insisted on an eye test that glasses were prescribed. The result was immediate: improved grades, restored confidence, and relief for the family.

Teachers see the daily toll in classrooms packed with pupils. Mr. Chokolo, a primary school educator in Abuja, described children who “miss everything from the back—sloppy writing, headaches, withdrawal. Parents often mistake it for laziness.”

From the stigma that glasses signal “weakness”, to sheer unaffordability, families battle invisible barriers while their children silently fall behind.

Expert Voices: Why the Crisis Persists

Eye health professionals point to changing lifestyles and systemic neglect.

Dr. Eze, an ophthalmologist in Enugu, explained: “Screens and indoor time accelerate myopia. Poor nutrition—low in vitamins A and E—makes matters worse. We are seeing more children needing glasses earlier and stronger.”

Evidence from the Nigerian Journal of Ophthalmology (2023) shows refractive errors in 15–20% of pupils, with higher rates in urban areas. Yet Nigeria has no national survey of under-18s, leaving policymakers blind to the true scale.

At the Federal Ministry of Health, specialist Mrs. Nneoma describes the crisis as “a pressing public health concern”. She cited alarming variations: up to 32% of pupils in southern states with visual disorders, compared with 6% in Cross River and 22% in the north.

“The leading causes are refractive errors—myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism. Allergic conjunctivitis is common, while severe but rarer cases like cataracts or optic atrophy rob children of sight. Yet many never get examined. In one study, just 1.8% of schoolchildren had ever had an eye test.”

Specialists are scarce, diagnostic equipment is missing in many hospitals, and insurance rarely covers paediatric eye care. “Without systemic change,” she warned, “we are locking out millions of Nigerian children from education and opportunity.”

Who Is Responsible?

Nigeria’s approach to childhood vision remains patchy. The absence of a national policy on school eye health means efforts fall to NGOs like Sightsavers or VisionSpring, which cannot scale nationwide.

Government figures recognise the gaps. With over 50 million school-age children, Nigeria’s sheer size demands coordinated leadership. Yet eye health is buried within broader health policy, with limited funding and almost no school-based mandates.

Contrast this with high-income countries where 90% of children undergo eye screening, compared with under 5% in Nigeria. The result is systemic inequality: wealthy parents seek care, while the poor wait until academic collapse forces desperate action.

Lighting the Path Forward

Experts agree the crisis is preventable. Key strategies include:

National Policy and Data Collection: Launch a national survey on childhood eye health and mandate screenings within school health services.

Subsidised Services and Insurance: Integrate paediatric eye care into Nigeria’s health insurance scheme, subsidising glasses for low-income families.

Public-Private Partnerships: Expand proven NGO models such as Seeing Is Believing across all states, training teachers to conduct screenings.

Awareness Campaigns: Use radio, TV, and social media to normalise glasses, reduce stigma, and alert parents to early signs.

Infrastructure Investment: Train more optometrists (current ratio: 1 per 100,000 people), equip clinics with autorefractors, and provide digital boards in schools.

Lifestyle Shifts: Encourage the 20-20-20 rule (every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds), outdoor play, and diets rich in vitamin A.

Such interventions could halve preventable childhood vision loss, saving billions in lost productivity while restoring dignity and opportunity to millions of children.

Seeing the Future Clearly

Nigeria’s childhood eye crisis is not inevitable—it is a matter of priorities. Every child squinting in a classroom, every parent unable to afford lenses, represents a failure of systems meant to protect the nation’s future.

As Mrs. Nneoma put it: “Early intervention can transform a child’s life. We cannot keep waiting until grades fall and hope for recovery.”

Glasses are more than corrective tools; they are enablers of learning, confidence, and national development. Unless Nigeria acts decisively—through policy, investment, and public awareness—the hidden epidemic of childhood blindness will continue to steal futures.

The time to see clearly is now.