KANO, Nigeria – In the quiet, dusty lanes of Hotoron Yan Dodo, Nassarawa Local Government Area of Kano State, the sound of grief hangs heavy. Inside a modest family compound, four small coffins were carried out within two weeks — each containing the lifeless body of a child from the same family. Hussaini Ibrahim Kafi, writes.

For Malam Yusuf Maitama, a father of five, diphtheria did not arrive as a medical statistic or a public health bulletin. It came as a fever, sore throat, and white patches in the throats of his daughters. It came as confusion and a desperate search for hospital beds. And it left behind silence — the silence of four children buried before their time.

Their story is not isolated. It reflects the larger failures of a health system struggling to contain a disease the world has known how to prevent for nearly a century.

What is Diphtheria?

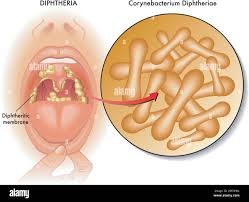

Diphtheria is a highly contagious bacterial infection caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. It spreads through coughs, sneezes, or contact with contaminated objects. The hallmark sign is a thick grey or white membrane that forms in the throat, leading to breathing difficulties. Without prompt treatment, the toxin released by the bacteria can cause airway obstruction, heart failure, or kidney damage.

The disease is preventable through routine childhood immunisation with the pentavalent vaccine — yet, in Nigeria, many children remain unprotected.

A Family Torn Apart

“The first was my youngest daughter,” Yusuf recalled, his voice breaking. “She woke up with a fever, sore throat, and catarrh. We thought it was minor. By evening, she was gone.”

Within days, her seven-year-old sister showed the same signs. Despite being rushed to the hospital, she also died. “That was the second child in one week,” he said. “Doctors confirmed it was diphtheria. That’s when I realised my other children were in danger.”

The two remaining daughters soon fell ill. One died at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, where overstretched wards and limited bed space forced the family to take her home. She died that very night. The fourth followed shortly after.

Only Yusuf’s eldest, barely a teenager, survived after urgent intervention. He cannot bring himself to say the names of the four he buried. “It is too painful,” he whispered.

Fear Across Hotoron Yan Dodo

The Maitamas’ ordeal has shaken their neighbourhood. Parents now live in dread, scanning their children for coughs and fevers. Health officials quickly fumigated Yusuf’s house and conducted emergency vaccinations for nearby families.

But the fear runs deeper. “Some people here still believe these illnesses are spiritual,” Alhaji Musa Ibrahim, a local elder, told Africa Health Report(AHR). “Others don’t know where to find vaccines. That is why diphtheria continues to spread.”

The Outbreak in Numbers

The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) confirmed that between 2022 and 2023, Nigeria recorded more than 10,000 diphtheria cases, with nearly 1,000 deaths. Over 70% of cases were in children aged 2–14 years.

Kano remains the epicentre, recording over half of national infections. Neighbouring states like Yobe, Katsina, and Kaduna also reported outbreaks, but Kano — with its dense population and low vaccination rates — has consistently suffered the highest toll.

A 2025 analysis by the National Library of Medicine found unvaccinated children were more than twice as likely to die from diphtheria compared to vaccinated peers.

Why Kano? Systemic Failures and Low Coverage

Why does diphtheria hit Kano hardest? The answer lies in systemic gaps. UNICEF reports that Nigeria’s national routine immunisation coverage for diphtheria-containing vaccines is about 56%. In Kano, the figure drops even lower.

Cold-chain breakdowns, vaccine stock-outs, and misinformation fuel the crisis. Many rural families either miss vaccination schedules or actively reject vaccines due to cultural fears and distrust.

A Kano-based paediatrician, Dr. Abubakar Garba Riruwai, explained: “We are seeing children arrive late, when the diphtheria toxin has already caused damage. Many parents delay seeking help because they mistake it for a common sore throat, or because they believe it is spiritual.”

Expert Analysis: A Preventable Tragedy

According to Dr. Riruwai, treatment depends on two critical interventions: diphtheria antitoxin and antibiotics. But antitoxin stocks are dangerously low in many hospitals, and parents often cannot afford the cost of care.

“Every death we see is a failure of prevention,” he emphasised. “Routine immunisation is the only sustainable solution. Emergency vaccination after outbreaks cannot protect everyone. We need to strengthen the system so that every child gets vaccinated on time, without barriers.”

Government and Partners’ Response

Kano State’s Ministry of Health insists efforts are ongoing. When contacted, Kano state Ministry of Health spokesperson, Nablusi Abubakar Kofar Naisa admitted most deaths occur among unvaccinated children.

“We urge parents to take their children for free immunisation. The government has designated special hospitals, stocked antitoxins, and continued mass vaccination,” he said.

The Federal Ministry of Health, with partners including WHO, UNICEF, and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), has rolled out catch-up immunisation drives across Kano and other affected states. Mobile vaccination teams, cold-chain investments, and public awareness campaigns are being scaled up.

But critics argue these measures often arrive too late. “It is reactive, not preventive,” said a health policy analyst in Kano. “The system waits for deaths before acting. Until routine immunisation becomes a priority, outbreaks will keep coming back.”

Numbers That Don’t Tell the Whole Story

While official figures highlight the scale, they rarely capture the full devastation. Behind every statistic is a family like Yusuf’s — burying children and left with unanswered questions.

The overcrowded Jidda Muhammad Hospital, currently the only designated diphtheria treatment centre in Kano, struggles daily to cope. Despite repeated visits, hospital management declined to speak with this reporter, underscoring a troubling lack of transparency.

What Needs to Change?

Experts outline urgent solutions to include scale-up vaccination campaigns in all LGAs, prioritising high-risk areas, strengthening routine immunisation, ensuring vaccines are available year-round, addressing misinformation by engaging religious and community leaders, and investing in PHC centres to bring vaccines and treatment closer to communities, and ensure steady antitoxin supply and train frontline workers.

If these steps are taken, Kano can reverse the tide. If not, more families may face Yusuf’s fate.

Beyond the Coffins

Four small graves in one compound should never have been dug. In a world where diphtheria is preventable, Yusuf’s story is not just a tale of personal grief — it is an indictment of systemic neglect.

For Kano, the choice is stark: continue reacting after children die or finally build a system that protects them before they fall ill.

Until then, the echoes of Yusuf’s loss will haunt his neighbourhood, a grim reminder that behind every diphtheria case number lies a child — and a future lost too soon.