[ad_1]

When Lagos-based investigative journalist, Kabir Adejumo contacted a chief in Ibeju-Lekki in Nigeria’s south western state of Lagos, he was not expecting a death threat to follow. He had reached out to the chief for a right of reply for his report following accusations that the chief raped a 17-year-old girl. But instead of giving his side of the story, the chief threatened the journalist.

“He told me he controls a lot of thugs in the axis and he knows that I live in Ajah and if care is not taken, I would be assaulted physically. I didn’t feel threatened but anytime I have to pass through the Ibeju-Lekki axis, it comes to my head: If this man or his people should see me, am I sure I would return home?” Mr Adejumo said to PREMIUM TIMES.

This was not the first threat the journalist has received from an alleged GBV offender. In another story in the same report, detailing how the police connive with accused rapists to frustrate justice for victims and survivors, Mr Adejumo narrated the experience of a family that accused their pastor in Lagos of raping their 15-year-old daughter for three years. He received a threat for this too.

While the traditional ruler threatened to kill the reporter, the cleric cursed and warned that he would “go spiritual to ensure I am not useful to my family,” said Mr Adejumo, the Assistant Investigations Editor at HumAngle.

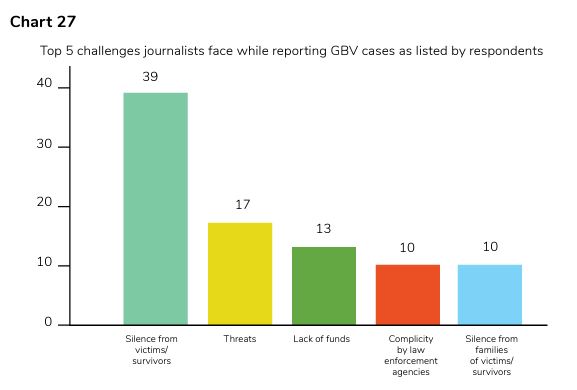

According to a 2022 survey published by the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) in its Gender-Based Violence Reporting Handbook, of 120 Nigerian journalists interviewed, threats were the second topmost challenge mentioned by those reporting GBV, after silence from victims and survivors.

While Mr Adejumo was threatened directly, Chioma Ezewanfor, a radio journalist at Nigeria Info in Port Harcourt, capital of Rivers State in the South-South region of Nigeria, said her organisation had been threatened with lawsuits by alleged perpetrators.

The most recent incident occurred in November 2022 when she interviewed a woman who accused her husband of domestic violence.

“We spoke to him on the telephone and he declined. He charged into our office and identified me and some members of my organisation and told us we will hear from his lawyers,” Mrs Ezewanfor told PREMIUM TIMES.

It didn’t bother her because she knew alleged perpetrators, “will do anything to prevent the story from going on air.”

Journalists facing attacks can get support through initiatives like AsariTheBot by CJID. The rapid response tool, which connects journalists to legal aid, is part of the Press Attack Tracker which documents attacks against journalists.

However, Busola Ajibola, Deputy Director of the Journalism Programme at CJID, said that attempts to offer legal support to journalists who need it have yet to be successful. Mrs Ajibola said that journalists who had previously indicated an interest in getting legal assistance through AsariTheBot later retracted their complaint or expressed a desire to settle the matter out of court for fear of reprisals.

For this reason, Mrs Ajibola recommended that newsrooms employ active legal teams to support journalists before and after the publication of their stories.

She also said there should be constitutional measures against people who attack journalists and added that CJID was mulling instituting a register of attackers, documenting their names and faces, sending them to global communities and embassies and tagging them as “enemies of democracy.”

Second-hand trauma

Besides threats, the journalists interviewed for this report said they also suffer psychological distress while covering GBV stories. This aligns with a report by African Women in Media, in which women journalists covering stories on sexual and gender-based violence said they suffer trauma in the line of duty.

Journalists covering GBV stories suffer secondary trauma from their sources and repeated exposure could morph into post-traumatic stress that manifests in various forms, according to Ayo Ajeigbe, Lead Clinical Psychologist, at Olive Prime Psychological Services in Abuja.

This was the case for Ene Oshaba, Head of the Gender page at BLUEPRINT Newspaper who covered a story on a 32-year-old man who kidnapped a 16-year-old. When the girl was found, she was pregnant and her abductor refused to release her.

The divisional police officer (DPO) told Ms Oshaba to drop the story and not to waste her time on the matter to avoid indirect threats.

“When he (DPO) told me that and upon seeing the expression on his face, I decided to drop the story. I am looking out for my family. I have little children and I do not want anything that will put me in harm’s way because I am a single mum,” she said.

While Ms Oshaba dropped the story, she said it affected her, not because the police declined to take action, but because she imagined her daughter in the shoes of the abducted girl.

“I could not believe this was happening because I live in the same town. I cannot imagine someone could hold my daughter captive, and get her pregnant. It replayed in my head because of the fear I had for my child,” said the stunned Ms Oshaba.

Like Ms Oshaba, Mr Adejumo was also affected by the report of the rape of the 15-year-old whose story he covered because the child repeatedly attempted suicide after the sexual violence.

“It took a toll on me particularly when I wanted to write the story as I had to replay the experiences of the girl in my head and her several attempts of suicide. I would start writing and the experiences would flash through my head. I had to stop and put it off. This happened repeatedly because I had to imagine what she went through to tell her story,” he said.

In spite of how he felt, he pushed the trauma to the back of his mind because he felt obliged to publish the story since the reporting was funded.

Neither Mr Adejumo nor Ms Oshaba sought professional help. They tried to forget and moved on to the next story.

Mr Adejumo sees the distress that arises from covering GBV stories as an occupational hazard and sees no point in seeking therapy. Ms Oshaba, on the other hand, now knows the dangers of not seeking help for secondary trauma, after attending a trauma workshop by PAGED Initiative, a non-governmental organisation that advocates for gender parity.

In CJID’s survey, 54 per cent of the 50 journalists who covered GBV cases said they experienced trauma in the course of their works, but only 11 per cent sought psychosocial care.

Mr Ajeigbe, a psychologist, said it is dangerous to ‘pile up’ unresolved traumatic incidents. He said that a journalist who does not seek professional help after covering stories on gender-based violence and traumatic events may unconsciously suffer post-traumatic stress which has an influence on their behaviour and relationships.

“Most people are experiencing post-traumatic stress but they do not know and it is affecting our day-to-day events,” said Mr Ajeigbe.

To tackle this, he advised journalists to attend debriefing sessions offered by psychologists immediately after covering the story even if they feel fine or participate in counselling or therapy sessions in the long run.

He also proposed that media houses consider the mental health of their staff and organise activities like team bonding sessions which will help the staff’s mental health and invariably improve their productivity at work.

Mrs Ajibola of CJID said that while the organisation has referred journalists for therapy sessions, newsrooms should incorporate mental health into their workflows.

“You (newsrooms) should be concerned about the mental health of your journalists. The job that journalists do is a very overwhelming job. What is the Nigeria Union of Journalists doing? What journalists experience has a direct impact on their mental health and they suffer a nervous breakdown in real-time,” she said.

A report published by IJNET observed that many newsrooms in Nigeria do not prioritise the mental health of their reporters. However, some organisations have conducted mental health workshops for Nigerian journalists, though these services are short-term and intermittent.

In South Africa, the South African National Editors’ Forum, partnered with a mental health services organisation to create programmes that prioritise wellness in newsrooms across the country. In the United States of America, a 2021 study found that comfort dogs were a coping mechanism for broadcast journalists covering traumatic events.

Low impact from reporting

Besides threats and psychological distress, journalists surveyed in the GBV reporting handbook decried the lack of justice after highlighting cases of GBV in the community. Of the journalists surveyed, 38 per cent said that justice was not achieved, a further 38 per cent were unsure, while only 24 per cent said that justice was served following their reporting. As a result, the journalists said that their stories had no impact.

Mrs Ezewanfor, News Manager at Nigeria Info radio station, said that less than half of the cases in the GBV stories covered by her newsroom ended in convictions and described this as discouraging and one of the downsides of covering GBV stories.

“You put in a lot of energy and effort but somehow it doesn’t end the way you want in getting justice for survivors. It is either the family pulls out and settles out of court,” she explained.

Likewise, Chika Mefor-Nwachukwu, a senior development reporter at Aljazirah Newspaper, said that she feels guilty when her story doesn’t lead to justice for the survivor, especially when the perpetrator continues with the assault despite being exposed.

In April 2022, the Minister of Women Affairs, Pauline Tallen, revealed that only 16 out of 5,100 GBV cases had ended in conviction. She attributed the low conviction rates to the slow judicial process and lack of funding of the fight against sexual and gender-based violence.

Lekan Otufodunrin, Executive Director of the Media Career Development Network, urged journalists to go beyond reporting and draw the attention of the authorities concerned to the published report as a way to address the challenge of low impact.

“They should also write a report when there is an impact by saying, after this organisation’s report, this impact happened. This would encourage sources to know that there could be impacts from reports,” he said.

He also proposed that media houses collate and evaluate published reports at the end of the year and seek alternative ways to follow up on the reported stories.

“When writing a report, we hope that there is an impact. But when there is none, be comforted you have told the story. The impact might not come immediately. It could happen years later when someone sees the report and decides to help.”

This is a strategy that Mrs Ezewanfor has taken to heart. Instead of feeling discouraged by the low conviction rates, she views her reporting on GBV as a means to document and archive the stories and to strengthen the conversations on GBV. “This is what has kept me going,” she said.

Family interference

Journalists covering GBV are also discouraged when families of survivors withdraw from the pursuit of justice. Princess-Ekwi Ajide, a broadcast journalist with Anambra Broadcasting service, experienced this while reporting on a 14-year-old who was raped by her teacher. The case was reported to the police and they visited the hospital to get more evidence.

However, upon subsequent follow-up, the survivor’s father told the journalist to stop working on the report. When she asked him if he had been threatened, he asked her why she was taking a painkiller for someone else’s headache.

READ ALSO: SPECIAL REPORT: In Nigeria, safe shelters are helping survivors of GBV

“I felt defeated. It was disheartening and I cried because it felt personal and the family did not understand the importance of reporting so that the man (perpetrator) will not do it to someone else,” the Anambra state reporter said.

The CJID GBV handbook explained that stigmatisation, victim-blaming, self-blame, fear of reprisal and lack of trust in the justice process are some of the factors why many survivors and their relations keep the trauma of the abuse and discontinue the process to prosecute the perpetrator.

Other barriers to covering GBV stories

Journalists interviewed for this report and the CJID GBV handbook also mentioned other challenges they face when reporting on gender-based violence, namely: accessing information from survivors, their families, the community, and law enforcement agencies; lack of cooperation and the unprofessional conduct exhibited by prosecuting agencies; editorial sabotage and lack of interest by newsrooms and lack of funds to follow up GBV cases.

The journalists called for these challenges to be addressed so that they can keep telling these stories with the hope of exposing the rot and getting justice for survivors through their reporting.

This article was produced as part of the WA GBV Reporting Fellowship with support from the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and through the support of the Ford Foundation.

Support PREMIUM TIMES’ journalism of integrity and credibility

Good journalism costs a lot of money. Yet only good journalism can ensure the possibility of a good society, an accountable democracy, and a transparent government.

For continued free access to the best investigative journalism in the country we ask you to consider making a modest support to this noble endeavour.

By contributing to PREMIUM TIMES, you are helping to sustain a journalism of relevance and ensuring it remains free and available to all.

Donate

TEXT AD: Call Willie – +2348098788999

[ad_2]

Source link