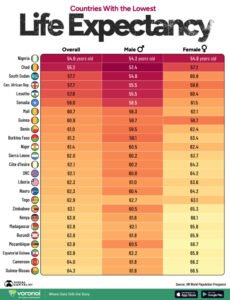

A newly released report by Visual Capitalist, based on the United Nations’ World Population Prospects 2024, paints a grim picture of global health disparities. Nigeria ranks last in life expectancy worldwide, with an average lifespan of just 54.6 years—54.3 years for men and 54.9 years for women. This stark revelation, reported by Korede Abdullah, Africa Health Report’s Southwest correspondent, underscores a deepening public health crisis in Africa’s most populous nation.

Africa’s Grim Longevity Crisis

A recently released chart by Visual Capitalist, drawing from the United Nations’ World Population Prospects 2024 data, paints a bleak picture: Nigeria ranks dead last in global life expectancy, with an average lifespan of just 54.6 years—54.3 years for men and 54.9 years for women.

This stark figure highlights the immense challenges facing the nation’s healthcare system, food security, sanitation infrastructure, and public policy. It also reflects a deadly convergence of factors: preventable diseases, high maternal and infant mortality rates, inadequate medical access, and rampant poverty, particularly in rural areas.

Paradox of a Country

Despite being Africa’s fourth-largest economy and a major oil producer, Nigeria fares worse than countries ravaged by protracted conflict and extreme poverty. Chad (55.2 years), South Sudan (57.7 years), and the Central African Republic (57.7 years)—all of which have faced civil unrest, economic collapse, or widespread displacement—still manage to record slightly higher life expectancies.

This suggests that economic size alone does not guarantee social welfare or effective healthcare delivery. In Nigeria’s case, systemic corruption, regional inequality, and underinvestment in health and education have created a disconnect between wealth and wellbeing.

Out of the 25 countries with the lowest life expectancies, 24 are located in Africa, overwhelmingly concentrated in sub-Saharan regions, where healthcare systems are underfunded, climate change has worsened food insecurity, and outbreaks of diseases like malaria and cholera remain persistent threats.

The only non-African country on the list is Nauru, a small island nation in Oceania, whose struggles with obesity, diabetes, and non-communicable diseases have dramatically lowered its average lifespan. The global pattern underscores not just a geographical divide, but a pressing moral and developmental challenge: the widening life expectancy gap between the Global North and South.

Gender Gaps and Hidden Contradictions

Africa Health Report (AHR) findings indicate that life expectancy is not only disturbingly low across these nations, but also marked by significant gender disparities that highlight underlying social and healthcare inequalities.

In countries like Mozambique and South Sudan, women outlive men by more than six years, a gap attributed to high rates of male mortality due to violence, road accidents, and occupational hazards, particularly in conflict-prone or rural regions.

Nigeria follows this global trend, albeit with a narrower difference of just 0.6 years, revealing subtler but still systemic issues affecting men’s health—such as late healthcare-seeking behaviour, untreated hypertension, and substance abuse.

“The data show that while women generally live longer, their extended lifespans often come with poor quality of life due to inadequate maternal care,” says Dr. Maryam Olawale, a Lagos-based public health analyst. She adds that “in Nigeria, 1 in 22 women face a lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes—among the highest maternal mortality ratios in the world.”

Compounded by limited access to family planning, postnatal services, and trained birth attendants, the longer life expectancy among women often masks the harsh realities of reproductive health neglect.

What’s more telling is that countries with significantly lower GDPs and fewer natural resources—such as Niger (61.4 years), Burkina Faso (61.3 years), and Guinea (60.9 years)—still manage to outperform Nigeria on this vital metric.

These countries, despite grappling with their own challenges, have made incremental public health investments, improved community-based healthcare outreach, and benefited from better-targeted international aid programs.

Nigeria’s poor performance, by contrast, speaks to a deeper governance crisis where rising income disparities and decades of policy neglect continue to undermine even basic health indicators.

Systemic Breakdown in Healthcare

Experts argue that Nigeria’s dismal life expectancy—hovering around 55 years—is a direct consequence of entrenched failures in the country’s public health infrastructure. Chronic underfunding, weak insurance coverage, dilapidated hospitals, and the erosion of rural healthcare services all contribute to an alarming mortality rate, particularly among women, children, and the elderly.

Maternal and infant mortality rates remain among the highest globally, while preventable diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and cholera continue to claim thousands of lives each year.

“Nigeria suffers from chronically underfunded healthcare, poor health insurance coverage, and inadequate access to rural medical services. The combination of corruption, brain drain, and policy neglect is deadly,” explains Dr. Charles Adeyemo, a public health specialist and UNICEF consultant while speaking with our correspondent.

“Even in urban areas, many hospitals lack basic equipment, essential drugs, or trained personnel, leaving patients at the mercy of overcrowded wards and out-of-pocket expenses”, Dr. Adeyemo lamented.

With less than 5% of Nigerians covered by national health insurance, and health expenditure consistently falling far below the WHO’s recommended 15% of the national budget—often hovering around just 4%—millions are left to fend for themselves. Public hospitals rely heavily on user fees, making medical care unaffordable for the majority living below the poverty line.

Meanwhile, the exodus of skilled health professionals seeking better opportunities abroad continues to cripple service delivery at home. Without a radical overhaul in governance, funding, and workforce retention, experts warn that Nigeria’s public health crisis will only deepen.

Conflict, Environment, and the Curse of Oil

Nigeria’s life expectancy woes are further compounded by insecurity and environmental degradation. Conflict in the northeast, farmer-herder clashes, and pervasive urban crime disrupt critical services like immunization, maternal care, and disease surveillance.

“Conflict zones see a collapse in vaccination campaigns, maternal care, and disease surveillance. It’s no surprise that life expectancy dips drastically in these areas,” Dr. Adeyemo adds.

Meanwhile, oil wealth—once seen as a blessing—has become a liability. “Resource wealth without accountability often results in what we call the ‘resource curse,’” says Dr. Oluwatosin Yusuf, a development economist. “Nigeria is a textbook case of how GDP growth can mask worsening human conditions”, he added.

Lessons from Neighbours

Nigeria’s decline is not inevitable. Neighbouring countries like Kenya and Madagascar have shown that political will, efficient public health spending, and partnerships with international organizations can extend lifespans even with modest resources.

“Political will and smart partnerships with international agencies have helped many African nations outperform Nigeria,” says Dr. Marie Gaye, a UNICEF health consultant in West Africa.

A multi-pronged approach—raising health spending, expanding insurance, tackling corruption, and focusing on women and children—can change the trajectory. As Nigeria stands at the crossroads, its leaders must decide whether to continue down this path or turn this data into a catalyst for lasting reform.