[ad_1]

By Bernard Assim- Ita and Samuel Gada (Lead Writers)

Editor’s Note: Reports from the 78th session of the United Nations General Assembly reveal that we are behind in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. But just how far off track are we?

As we strive to achieve the ambitious goals laid out in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, it becomes increasingly evident that the future we envision for our children is far from guaranteed. At the heart of this concern lies a vulnerable group that demands our immediate attention — street children. In recognising that children are the cornerstone of any nation’s foundation and its future, it is crucial to acknowledge that Nigeria as a nation and as a society, is failing to protect and uplift these young lives with the alarming number of street children across the different regions in the country, from north to south, and east to west.

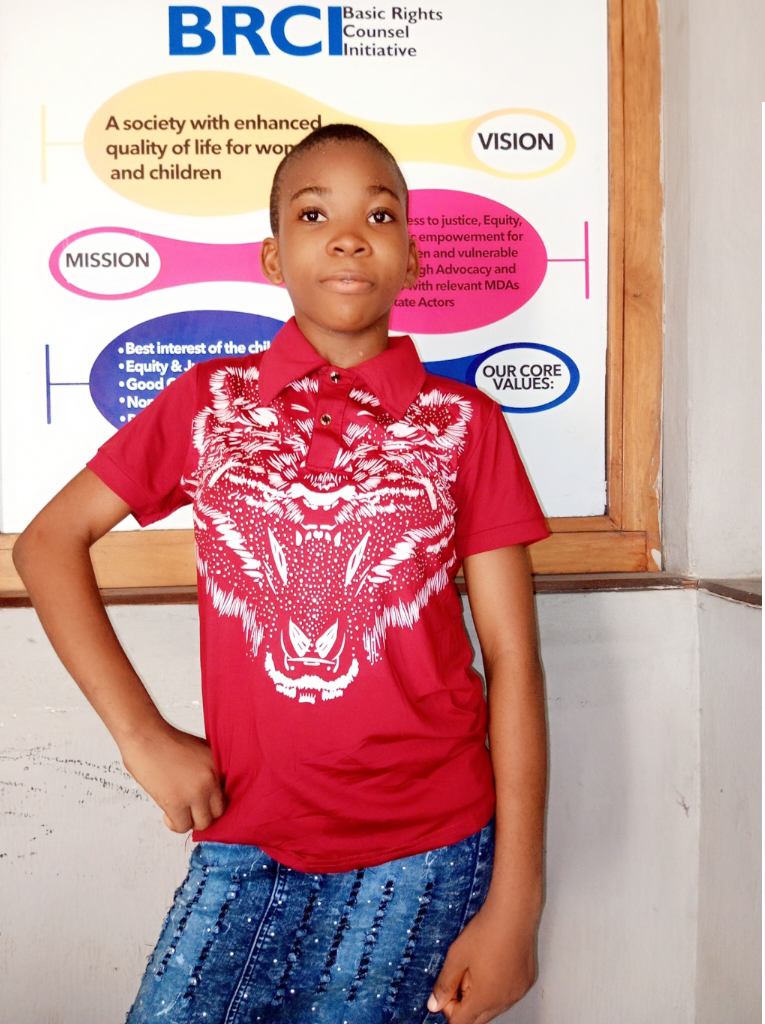

Lurking around almost every corner in Calabar, Cross River State, you can find young children like Daniel without a home who are exposed to harsh living conditions, malnourished, and with poor access to basic sanitation, healthcare and education.

According to the United Nations, there are up to 150 million street children in the world. In Cross River State, Nigeria the population of children on the streets soars daily. These children inhabit abandoned buildings, garages, and markets. There are many reasons that these children end up on the streets, including hunger, poverty, and the need to escape from abuse and other family situations like polygamy. To further exacerbate the issue, the children are referred to as “Skolombo” a local parlance that refers to children abandoned or sent away from home.

In 1990, Nigeria ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and in 2003, the Child Rights Act was enacted, outlining the responsibilities of children and the obligations of the government, families, and authorities in protecting their rights. In May 2009, the Cross River state government passed the Child Rights Act and declared the state safe for children. Unfortunately, the overwhelming presence of street children makes this claim untrue.

A coalition of Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) assembled under the brand “Youth Serving NGOs” in 2019 set out to rehabilitate and reintegrate these children into society by providing them with water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services, health care, and social empowerment. The coalition comprises of the Medical Women Association (MWA), Basic Rights Counsel Initiative (BRCI) and Street Priests, amongst other NGOs in the state. The Youth Serving NGO was set up to ensure efforts to maximise outreach impacts for the children on the streets addressed the children’s various needs.

“Each member of the coalition responds to at least one pressing need of the street children,” James Isibor, Co-founder of Basic Rights Counsel Initiative (BRCI), shared.

BRCI was founded in 2011 in response to the alarming rate of vulnerable children on the streets, most of them were victims of child abuse, being branded as “witches” or “wizards”. The absence of family courts and specialised organisation to carry out case management and advocacy for the rights of these children was the motivation behind the establishment of BRCI. The organisation also offers a holistic response to incidences of violence against children and collaborates with the State Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs to rescue children from unstable and harsh family situations.

Religious leaders have also been known to contribute to the number of children on the street, defrauding unsuspecting parents and guardians into believing children are “witches”. According to Isibor, most of the children were expelled from their homes and branded “witches” and “wizards”. “Reintegrating children or getting foster care services for these children who are branded witches is very difficult because they’ve already been stigmatised as witches, so you hardly find foster care for them. Sometimes it is dangerous to reintegrate them back to the families that stigmatise them to avoid continuity of a vicious cycle,” Isibor said.

So far, BRCI have engaged with a total of 843 children, supported the passing of four bills that are child-centric and aided the conviction of 15 child rights offenders. They are also reunited children with their families, enrolled children into foster care and supported the adoption process for children in the state. One such case is that of Faith and her sister, who were rescued from their father in the Akansoko community of Akpabuyo where they were tied, starved, and denied access to other people in their community because they were accused of practicing witchcraft.

Rev Ibe Orji Mba, who adopted Faith Orji Mba with the help of BRCI said that “Faith is our first child, she is the madam of the house, when her mommy is not around”.

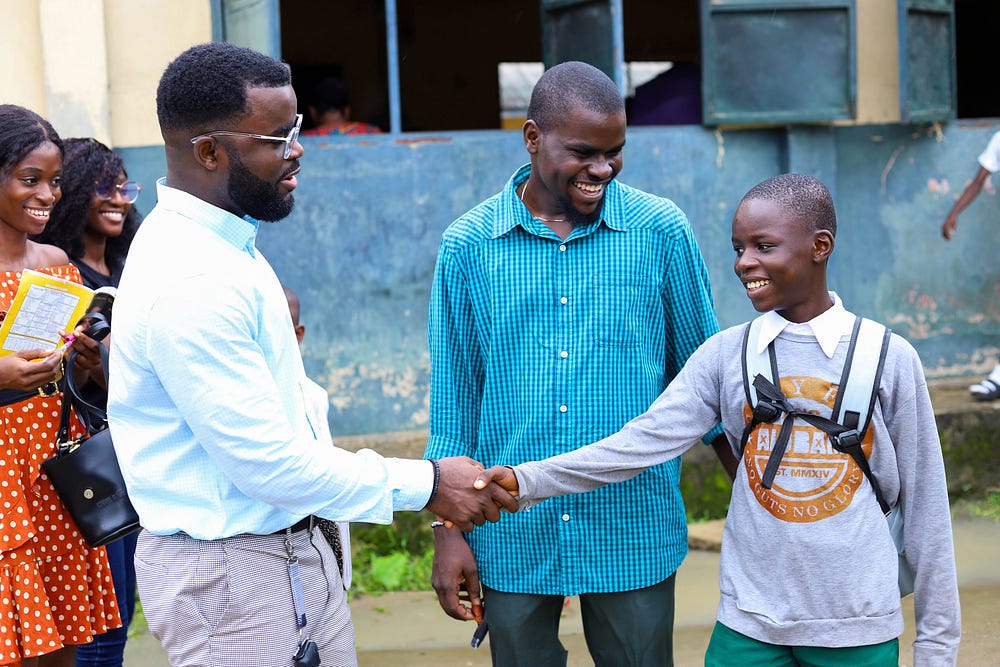

Street Priests, on the other hand, provide social empowerment, rehabilitation and reintegration of children on the street into society. The organisation has implemented a “Back-to-School” programme with a comprehensive mission to engage, equip, mentor, and rehabilitate children, addressing issues like illiteracy, which often leads to homelessness, poverty, and the influence of religious superstitions.

The programme also adopts an in-depth mental, emotional, and physical evaluation approach to ensure that these children are well-prepared for the academic journey ahead of them. Their 2023 Back to School Conference highlighted the multiple talents of the children who participated in panel discussions, contributing to engaging entertainment, and serving as hope for children still on the streets.

Besides the “Back-to-School” programme, Street Priests also runs regular health outreaches and periodical check-ins with the children. Miracle Emmanuel, the Storyteller and Communications Officer at Street Priest shared how they have discovered many ill children during these outreaches.

The health wing of the Youth Serving NGO is under the management of the Medical Women Serving Association Calabar branch and operates on need bases. According to Dr Ranti Ekpo, Coordinator, Health Wing, Youth Serving NGO, the children are divided into zones within the different areas of the metropolis in Calabar. There are members of the association who are professionally equipped to oversee the welfare of the children in the identified zones and respond when there is a health challenge. The health wing of the coalition also carries out comprehensive sexual education session, informing the children how to avoid STDs like HIV/AIDS.

Medical Women Association Calabar also creates a sense of belonging and community for street children, as a step to rehabilitate and aid the reintegration of children on the streets into a more befitting society. This included carrying out health and enlightening outreaches to educate the children on the importance of good sanitation and hygiene.

Despite the progress, challenges persist, such as the relapse of beneficiaries, particularly children already addicted to substances. “Reintegrating these kids with their families is not a total problem. The issue is that most of them, even within our facilities, are already struggling with addiction challenges and are used to the carefree life, so putting them in a regimented system often fails,” Dr Ekpo said.

Funding is also a significant challenge affecting the frequency of the outreaches. According to Isibor, the outreaches have now been reduced to specific holidays, excluding occasions where individuals provide support.

According to the latest report from the UN Development Programme (UNDP), Nigeria, is ranked 163rd out of 191 countries and territories on the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) for the second consecutive year.

By addressing these children’s health challenges, providing education, and reuniting them with their families we can accelerate progress toward achieving SDGs and improving human development. To sustain and expand these positive impacts, collaborative action is essential. Initiatives like the Youth Serving NGOs and others like the Alaba Market mentorship model, where rehabilitated street kids mentor others, should be replicated to create a supportive ecosystem for children on the streets.

[ad_2]

Source link