[ad_1]

By Kenneth Ibe and Kemisola Agbaoye (Lead Writers)

Primary healthcare is the cornerstone of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and is the first port of call for individuals and families seeking healthcare. Nigeria’s primary health care system is fraught with numerous challenges, one of the root causes of which is that it is primarily the responsibility of the Local Government, the weakest tier of government in Nigeria. Decades of poor political will and financing to improve the quality of care available at the community level have caused the public to become disenfranchised with Primary Health Centres (PHCs), as only 20% of the 30,000 PHCs in Nigeria are functional even though more than half of Nigerians access healthcare at public facilities.

Enugu State — taking responsibility for improved Primary Health Care for her people

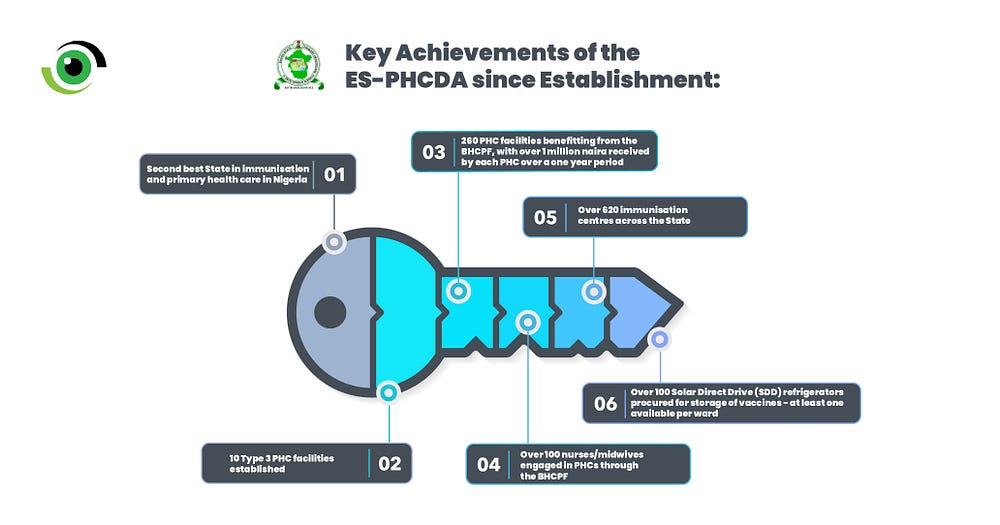

Enugu State is no stranger to these challenges as the state’s PHCs were fraught with poor infrastructure and inadequate personnel and equipment, according to Dr George Ugwu, Executive Secretary of the Enugu State Primary Health Care Development Agency (ES-PHCDA). How then did the State become the second-best in childhood immunisation in 2021 and the second-best in primary healthcare service delivery in the country, as indicated by the State of States on PHC delivery report? Dr Ugwu attributed this outcome to several factors, beginning with a strong political will that created a conducive environment for policies and funding to bolster the state’s primary healthcare (PHC).

An enabling environment for PHC reforms

The Enugu State Healthcare Reform Law, signed in 2018, established the ES-PHCDA with the mandate to ensure “a healthy Enugu State”. As Executive Secretary, in 2019, Dr Ugwu established six units to effectively coordinate and supervise all primary healthcare activities in the state. He then appointed staff to Head the various units and developed a roadmap for improving primary health care in the state. “The health care reform law, which His Excellency established, laid the foundation for our work. He appointed me to lead this effort, and I give him credit for his vision and support. I have been dedicated to fulfilling his expectations and ensuring the success of our initiatives.” said Dr Ugwu.

With over 620 immunisation centres spread across the state, effective implementation and oversight of primary healthcare activities require a well-coordinated mechanism. He attributed his ability to move quickly and effectively to an agile communication culture with the Executive Governor of Enugu State, Honourable Ifeanyi Ugwuanyi, his management team within the agency, and donors and partners.

Moreover, Dr Ugwu credited the Governor for his unwavering political will and commitment to prioritising primary healthcare. According to him, the Governor made resources available, particularly for those in hard-to-reach rural communities, due to his keen interest in their health. This shows, again, that UHC is a political choice and underscores the importance of cultivating political will and champions, one of which (in this case) was the First Lady of the State, Monica Ugwuanyi, a vocal advocate for women and child rights.

In developing a roadmap for the improvement of PHC services in the state, Dr Ugwu made sure to plug into national health programmes, including the Primary Health Care Under One Roof (PHCUOR) policy, which was established in 2011 and aims to ensure integration of PHC services and reduce fragmentation, thus increasing efficiency. He also plugged into national outbreak management policies such as the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) structure and enjoyed a good relationship with the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA).

Improving infrastructure and manpower for quality PHC services

To bridge the infrastructural and human resources for health (HRH) gaps in PHCs in the state, the agency did two major things;

1.Establishing Type 3 PHCs:

Driven primarily by state government allocations, these centres were designed to provide rural communities with comprehensive healthcare services, including preventive, curative, and promotive care. Patients can access diagnostics and treatment of common ailments and maternal and child health services, including immunisation and family planning services. These centres, strategically located in hard-to-reach communities, are equipped with modern medical equipment and facilities and staffed by skilled healthcare professionals, including resident medical doctors and nurses, addressing one of the major barriers to retaining healthcare workers in rural areas.

The journey to establishing these Type 3 centres started with renovating existing facilities. A total of four centres were upgraded to Type 3 status, setting up separate wards for different demographics, accommodation for resident doctors and nurses, and essential amenities such as potable water and stable power supply while maintaining a uniformed green roofed building structure. The goal was to renovate as many centres as possible, based on the available funding.

So far, seven new Type 3 primary care centres have been completed and commissioned to provide services, while three centres have been completed but are awaiting commissioning. This brings the number of Type 3 facilities in the State to 14, spread across Enugu East, Enugu North, and Enugu West Senatorial zones.

At least two doctors, four nurses/midwives, and other supporting staff are employed per centre. To promote staff retention, the ES-PHCDA collaborated with community leaders to ensure that health workers are recruited from the LGAs. In addition, health workers and supporting staff are required to sign agreements committing them to remain in their respective facilities for at least three years.

The centres are fully equipped with the necessary tools, including theatre equipment, to ensure comprehensive medical care. Furthermore, each centre has its borehole, independent electricity supply, and a well-equipped gym. This comprehensive approach creates functional health facilities where doctors reside on-site, providing round-the-clock care.

A beneficiary from the Type 3 Primary Health Centre in Udenu Local Government Area (LGA), expressed her satisfaction with the high-quality maternal health services she received during her caesarean section. She emphasised the rarity of such exceptional care, saying it was unparalleled in any other primary healthcare centre in Nigeria. “I found something special in this Type 3 Primary Health Care center. They provided me with really good care and made sure everything went well when I gave birth. This is not something that happens often in other similar centers around the country.” she said.

2. Plugging into the Basic Health Care Provision Fund

The Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), a Nigerian government initiative aimed at providing UHC by allocating funds for essential health services, was instrumental in bridging HRH and other resource gaps in PHCs across the State. But first, Dr Ugwu had to convince the governor that it was worth doing. “By highlighting the immense advantages of the BHCPF to His Excellency, his unwavering support and substantial investments in primary healthcare led to the resounding approval and successful implementation of the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund in our state,” said Dr Ugwu.

Enugu State was approved to commence implementation of the BHCPF in 2021, but an array of requirements preceded this — they had to open bank accounts for PHCs, set up Ward Development Committees (WDCs) for monitoring and accountability and conduct a series of training for PHC staff. Of the 518 functional PHCs in Enugu State, 260 are benefiting from the BHCPF and through the fund, 100 midwives have been engaged, over NGN 200,000 in funds are disbursed to each PHC per quarter, and each PHC has received over 1 million naira since the commencement of implementation, all within two years.

Demand generation and community engagement

To increase demand for PHC services and monitor service quality, ES-PHCDA engages communities through the Community Health Influencers, Promoters, and Services (CHIPS) programme — another national health programme that the state plugs into — and other demand generation and feedback mechanisms. They foster a strong relationship with community leaders and encourage feedback via phone calls, SMS, etc. They leverage community structures such as town criers and local immunisation officers to increase demand for services like immunisation, especially during infectious disease outbreaks. The ES-PHCDA also leverages the media to engage with communities.

This is worth noting as primary health care improvement programmes often de-emphasise the demand side and ignore the critical role that communities can play in promoting accountability, as demonstrated by the Nigeria Health Watch Community Health Watch project. According to Dr Ugwu, the state has enrolled over 100,000 lives into the BHCPF through the State Health Insurance Agency (SHIA) — evidence of strong demand generation and synergy in the efforts of both agencies.

Mitigating the human resource challenges in PHCs

One of the foremost gaps to bridge in PHC service delivery in Nigeria is the insufficient human resources available at PHCs, a fact corroborated by Dr Ugwu when sharing some of the limitations and challenges of the PHC reforms in Enugu State. He cited inadequate funding to attract and retain staff, poor attitude of healthcare workers, brain drain and irregular supportive supervision mechanisms as major barriers to providing quality healthcare in the PHCs.

The fact that the Local Government Authorities manage the PHC staff significantly hinders his ability to adequately sanction and regulate erring staff, which has prompted him to explore policy options that will put PHC staff firmly under the purview of the ES-PHCDA. According to him, the agency is working to assume full responsibility for them, including payment of their salaries. This would help curb inefficiencies, including absenteeism of staff posted to the PHCs — a major problem in most PHCs.

The ES-PHCDA employs a supportive supervision approach, which includes unannounced visits to PHCs, according to Dr Ugwu. Studies conducted in the state have shown that internal (within facilities) supervision mechanisms are more effective in reducing absenteeism and reviewing the approach for external supervision into supportive and collaborative, as opposed to sudden, unannounced “fault finding” missions, could be beneficial. The state is also exploring digital options for the institution of supervision and monitoring mechanisms, which could significantly improve performance.

Looking Ahead: Becoming Number One in the Country

According to Dr Ugwu, the state is proud of its achievements but will in no way relent in its efforts to become the best in the country in primary health care delivery. There are still several PHCs that need upgrading, and he is keen to explore feedback mechanisms to upgrade both functional and non-functional PHCs in the state. He recognises that cultivating strong political will, leveraging national health programs and community engagement has worked, and looks forward to building on these successes to achieve #HealthForAll for the people of Enugu State, particularly in light of a new governor assuming office.

[ad_2]

Source link