[ad_1]

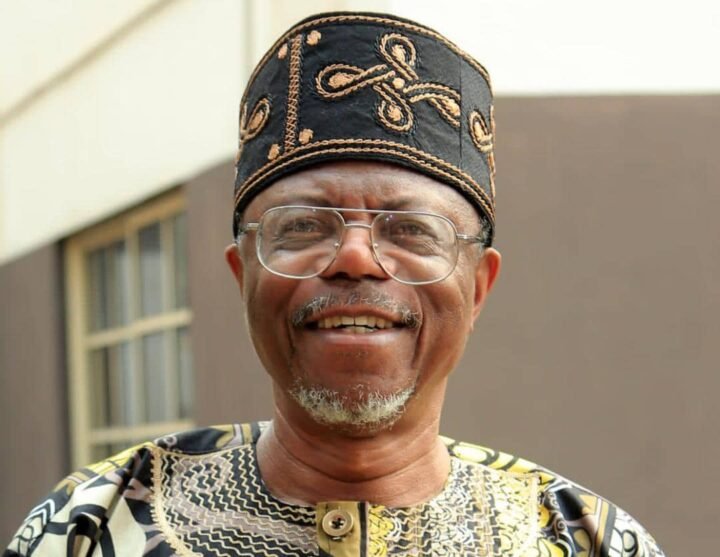

Born on January 1, 1953, in Ibadan, Nigeria, Toyin Falola, award-winning academic and author of over 200 books, in this interview with RITA OKONOBOH, speaks on turning 70, his experiences as a scholar and historian, and issues around politics and education reform in Nigeria.

TheCable: At 70, what would you wish to change about your life?

Falola: I will leave all the positive values alone because they are too many. Twice, I’ve asked myself: I enjoy drinking, but why do I drink? Maybe I may say ‘okay, it’s a bad idea for me to drink because of the health consequences’. The other thing is not to keep too many friends. You can have colleagues, church members, and associates, but be careful about what you call friends, because they trigger issues of jealousy, issues around resentment.

But bottom line, whether you have friends or not, the more successful you are, the more people want to bring you down and the more lies they generate around you. The Yoruba will resolve it by saying ‘take it easy; even your siblings will betray you’.

TheCable: What career path would you have taken if you were not in academia?

Falola: You have to know I’m very restless. When I was young, at Ife, they misunderstood this talent. I’m very restless. For instance, in 2023, I’ll release two books on social media; they are already in the press. I’ll release two memoirs. In January, I’ll release a book on refugees. Scholars don’t work like that. I write on literature, religious studies, sociology, economics; same thing with my career interest. When my mates were in secondary school, I completed a diploma in journalism and in salesmanship. That tradition is dead. In the sixties and fifties, there was an established tradition of external degrees.

And then, working with my fingers. My father was a radio repairer and a tailor. We also like to work with our hands. Everybody should learn to do something with their hands. Even when I decided to go to university, they admitted me in five major universities, but I did not apply for the same subject. So, we call it an embarrassment of talent in which I could draw, write poems, do short stories, book illustrations; what I’m wearing is my design. I can do many of those things.

The fundamental premise, since the age of 12, nobody has given me money to eat. I just believe in self-empowerment. Now, I’m even thinking ‘what do I do next?’ You’ll be surprised that I’m thinking maybe I should establish a non-fee high school — that people would go to school for free. That’s one possibility. But I’m struggling to see what can I establish, not to make any profit, but for people to benefit from.

As I enter the last phase of my life, I’m struggling; I want to become a missionary of something. I do a whole lot of peace work. There is also what is missing — community leadership. There was a tradition of community leadership; that is also dead now. All societies need community leaders — those who can resolve conflict, resolve issues, advise young persons, and be a moral centre holding that community together. I’m also thinking ‘why can’t I work on that?’

TheCable: The Centre for African Studies at Cape Town University describes you as an intellectual legend. Do you see more intellectual legends from Nigeria in the future?

Falola: Every generation produces its own thinkers, intellectuals, and writers. Actually, I’m in awe of this generation. I worship them. I don’t do mainstream thinking, because mainstream thinking produces consensus that lacks validity. It is actually not true that we have overproduced this generation; they have overproduced us. The media is different; they write more on social media than my generation writes books. There is no area of talent that they’re not competent in — short stories, creative writing.

But I’ll approach this topic in two other ways because an avenue like this is also to demolish mainstream thinking. Trashing these young people is not correct. Nigerian youths are so good with coding. Not far away is Computer Village and they have created what we call the Yaba Valley — extremely IT-savvy, intelligent, and brilliant. But instead of making these things grow, we call them crooks and ‘Yahoo Yahoo’. I’m not saying there are no bad ones among them, but we are exaggerating it and not tapping into those possibilities.

The true fundamental theories now shaping the humanities are not from my generation, not from Achebe, not from Senghor, not from Wole Soyinka; it’s from young people and we are not giving them credit. Ideas far more profound than what many of their predecessors have done. What are these ideas? Afropolitanism and Afrofuturism — those are the driving intellectual energies of the moment. And the entire terrain of science fiction, in which they take juju and ‘babalawo’ writing and convert them into ‘Wakanda’. My generation could not have done ‘Black Panther’. Why do we now have that cluster of talents and we trash it?

Modern-day contribution of Africa to the world is from music and youths are the ones. The third biggest film industry is Nollywood, and it is from younger people. Finally, the global revolution in clothes, attire, dressing, and writing. If we can figure out how we can begin to trust this generation, further empower them, incubate what they do, invest in what they do, convert what they do into entrepreneurship and business.

TheCable: With your experience as a historian, what would you suggest on addressing the ASUU strike once and for all?

Falola: There is no once-and-for-all there. There is still going to be ASUU strike. There is nothing peculiar about Nigeria with the ASUU strike. You can’t have the highest concentration of your scholars and intellectuals; that’s where you’ll get the density of your protests from. Not only because they know their rights, but because they can say ‘give us the privileges of elitism’. So, that protest is not going anywhere. It’s just going to be delayed. You cannot say they should not enjoy part of the privileges of the elite of a nation. Secondly, by the nature of their job, salary is just one component of it. Unless you say ‘we’ll call you a professor that has not published’. We want to say you must publish before you become a professor, then you have to put the resources down. That research money has to come from somewhere. We cannot be asking them to apply abroad. We have to manage TETFUND to be more responsive to that kind of thing.

Are there other things that can be done to reduce the strike? They can say, ‘as a union, we will focus on our welfare’; ‘let students pay school fees’ so they can use that money to run the schools. The federal government can also say ‘councils and senate, manage your universities the way you like’, so that they are fighting the senate and councils instead of fighting the federal government. The third point: Why must we have a centralised single university system — NUC? Why don’t you decentralise it? Why is it that the laws that apply to public universities apply to state universities? We have to rethink that and part of what I’m suggesting is that when a new administration comes in next year, part of the very first thing it should do is to convene a retreat on higher education and concretise policies that will stabilise the university system. But of course, you are aware that politicians don’t send their children to our schools.

TheCable: The house of representatives recently organised a summit on education reform and there were varying views on funding education. Do you agree with the concept of student loans?

Falola: Historically, Nigeria did it before. People forget that in the 70s, the Gowon administration did loans for university students — lots of money then. But they did not have the mechanism for people to pay back, and people were not paying back. Sometimes, they will go to the newspaper and list the names of those who were owing. Eventually, they phased it out. They may have to go and study models, as in the US model, where it is the banks, not the government, that give those loans. They have a way of collecting their money back. What the federal government does is say ‘we will not let you use high interest rates, and we will assist some to pay back if they accept certain terms’. Like, in 2022, the Biden administration gave $10,000, which they will transfer to the banks to offset some of those loans. Or they will say those owing can work in certain areas, and the loan will be forgiven. But until they figure out how to collect their money back, the idea of a loan is not going to work.

TheCable: With recent speculations over the number of Nigerians moving abroad, should the country worry about the ‘japa’ trend?

Falola: We should worry. The biggest asset in development is human capacity. It is not oil; it is not gold. It is knowledge economy and human capacity. And the more you lose that human capacity, the more you are undermining yourself. There have been three waves in the movement of our people outside Africa. The first wave produced the African American identity, Afro-Brazilian identity — they took over 30 million people away by force? Why? For muscle power. The second wave was voluntary — diaspora of colonisation. People were looking for opportunities.

The current wave, in which African economies are not doing well, and in the case of Nigeria, compounded by insecurity in which they are no jobs internally, and those jobs that exist, the pay cannot meet their minimum standard of living. People want to leave. The people who leave essentially are the skills needed in other parts of the world, which are also the skills you need to transform your own society and make life better for your own people. We have to worry.

Two things that provide assent to that worry — the first is you use your resources to educate them. You go to the University of Ibadan, where you pay very minimally to become a doctor. Instead of your nation now benefitting from that investment, UK benefits from it. The second worry, a developing country is now a source of technical assistance to a developed country. How can we now be the ones subsidising? How can it be we — marginalised, poor, struggling — that are now producing professors, engineers for the US?

TheCable: From what you know of Nigeria’s political history, do you believe in zoning?

Falola: I have to interrogate the origin of zoning. It led us to military coups, civil war. You have to distribute power in a plural society. A plural society is very difficult to manage. So, you must figure out a distributive mechanism of power. Otherwise, you are going to create resentment that will destroy the nation.

In any plural society at one given time, you’ll find centrifugal forces at work. Sometimes, the forces will bring them together, such as when they’re playing soccer. Nigeria has not produced any hero in its history because your hero is not my hero. Plural societies cannot produce heroes like that. There was a time they united over Dick Tiger, the boxer. Wole Soyinka, a Nobel laureate, is very popular but that’s outside of your country, and don’t forget, he’s a south-west figure. Chinua Achebe is an Igbo hero — he wrote ‘There Was A Country’. So, you’ve not even produced intellectual heroes talk more of political heroes.

So, you can give it another name, but you can’t say you’re not going to do what looks like that zoning. Peace is not cheap; it is very expensive. People have to remember that. Peace does not mean the absence of conflict and problems; it just means the capacity to manage conflict. A nation is like a marriage. Two marriages are not the same; two families cannot run the same way, and the same for nations. So, fundamentals of zoning, give it another name, you must empower everybody. For instance, suppose I were an Igede man, Idoma, Ebira, I’m not going to be happy because but for military rule that brought the middle belt to power through coup, and Obasanjo that facilitated Jonathan, the minorities have no chance at all. So, how do we have a nation in which ‘I’m Kanuri, Tiv, nothing for me’. That’s not going to work. You are producing millions of enemies within your nation.

TheCable: What is your assessment of the current crop of presidential candidates?

Falola: My assessment is that I have no candidate. But suppose I had a candidate, it means nothing because Nigerians keep deluding themselves into thinking that this messiah will come. I think one philosopher said the definition of madness is repeating what you’re doing that is not working. I think our problems are institutions; they are not strong enough. But who created these institutions? One time, we created a team through my series on ‘suppose you want to find an alternative party’, and I called Jega when they wanted to float the idea. I found that it would cost you over N200 billion to float a new party, establish structures, meet them money for money. Do you know on the day of the presidential election, in 175,000 polling units, you need close to $2 billion that day alone to man the polling booths?

Do you want to change the system? Chinese models? This democracy is not working and the earlier we realise it and begin to think about either we modify it or look for alternatives, the earlier we are going to save ourselves from future problems. We are going to have a new president. I wish them all well, but I don’t see much coming from the candidates.

TheCable: You talked about the need for strong institutions. Recently two ex-governors who were imprisoned for corruption were granted state pardon. Do you think Nigeria’s laws are strong enough to fight corruption?

In the law book, yes. But in practice, no. The Chinese model — get caught, get killed; the Japanese model, get caught, commit suicide; the American model, go to prison for twenty-something years. And none of that is working. And the reason why it is not working is that the one who can make it work knows his own secret. The person who can do the judicial penalty knows the ‘Ghana-must-go’ under his bed. The person who will take you to jail knows what is in his fridge and cemetery — the stolen money. So, everybody knows they’re thieves. It’s only the bad luck of one caught momentarily, and they are already saying ‘let us release one of our members’. I’m sure they would be joking about it so that when it comes to your turn, they will also release you. So, it’s a relay.

TheCable: Do you think Africa is doing enough on telling its own stories?

Falola: We have to separate creation and content from their publicity. Are we generating content? I think we do generate content. Do we have the avenues to circulate, publicise the content? That’s where the problem lies. Social media is doing that but it’s not going to be enough because social media does not have a reward system. There is a sense in which reward system validates content and literary production. We have an abundance of talent, but we do not have an abundance of opportunities. Human beings respond to incentives. That’s why we make a distinction between hobby and career. So, I’ll say it’s a function of incentives and failure of the reward system — not a function of intelligence and capacity. People will create more if they have the motive to do so.

[ad_2]

Source link